On October 1st, Ecuadorian President Lenin Moreno announced a series of economic measures for the country, including the elimination of gasoline and diesel subsidies and the liberalization of their prices, as part of an agreement with the International Monetary Fund (IMF). These measures led to the eruption of massive nationwide protests for eleven consecutive days, which were met by the government with fierce repression. Despite the repression, protests did not yield and ultimately made the Government back down and derogate these unpopular measures. The protests in Ecuador have important lessons for thinking social justice in environmental policies, and climate policies in particular. As history has shown us several times, when environmental policies are not thought through from a social justice perspective, they can only serve to perpetuate inequitable structures and marginalize the most vulnerable. The field of political ecology research has been vast in this regard. We have seen how conservation policies in national parks marginalized thousands of people inhabiting those spaces, or how new circular or innovation economies, presented as environmental fixes, do not really respond to the structural problems of the capitalist system that fosters economic growth, the expansion of the extractive frontier, and the increase in global pollution. Among the environmental fixes proposed to combat climate change is the elimination of fossil fuel subsidies. The logic is simple, but, as I’ll explain later, wicked: by eliminating the subsidy, the cost of fossil fuels increases, which would result in a relative decrease in consumption and, thus, less pollution and carbon emissions. It could also encourage technological innovation for renewable energy and clean combustion vehicles. But if those fixes are implemented in a highly unequal society, as the Ecuadorian one, the next question should be: if the high cost of fuels can restrict consumption, who would then have the capacity to maintain the same levels of consumption and who, with limited purchasing power, would be restricted? And what are the consequences of this? Unfortunately, those proposing these kinds of environmental fixes rarely ask these questions. This tells us that environmental policies that do not tackle social inequalities are problematic, especially because “wealthier people, even the environmentally-aware ones, produce more carbon pollution”. Here’s an example of this kind of wicked logic. A study conducted by the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) published in June this year, mentions that replacing fossil fuel subsidies with higher social spending in Ecuador can become an effective tool with triple results: addressing climate change, improving social conditions and solving the country’s fiscal problem. This proposal stems from the argument that, in the past 10 years, Ecuador has spent 7% of its national budget to subsidize fossil fuels in the country. If the government withdraws these subsidies, the social investment deficit and the country’s accumulated debt could be alleviated. To support the environmental argument, the publication cites another study carried out by the IMF in May this year, explaining that the emission of greenhouse gases and other environmental costs are greater than the fiscal cost of maintaining the subsidy. However, estimations for Ecuador are not included in this analysis. Perhaps ironically, these same organizations have promoted devastating structural adjustments in highly vulnerable national economies across the world. In March of this year, the Ecuadorian government signed a letter of understanding with the IMF to receive US $ 4.2 billion in loans to cover the country’s fiscal deficit. Among the conditioning economic policies imposed, are structural reforms to eliminate subsidies for gasoline and diesel. That represents a price increase of 29.7% for gasoline and 123% for diesel, the latter used massively for public transport, heavy transport of goods and for agricultural machinery. This measure directly affects the subsistence economies of middle-class and poor families in Ecuador by increasing public transportation costs, and would have an inflationary effect on the production costs of food and other daily consumption goods. The national government never positioned the structural adjustment from an environmental standpoint, but an economic one. Heterodox economists in Ecuador however have warned that the increase in the costs of goods, together with the decrease in the purchasing power of Ecuadorians due to this measure and other neoliberal economic policies taken by the national government, will have an effect on the country’s productive capacity, which will result in a vicious cycle of increasing poverty. This economic phenomenon, together with the reduction in public investment, seriously jeopardizes people’s actual living conditions and therefore negates the IDB’s argument that the elimination of fuel subsidies can create social benefits. In fact, the IMF’s structural adjustment policies have destroyed national economies across the globe. Research published this year analyzed the structural adjustment policies imposed by the IMF between 1980 and 2014 in 135 developing countries and showed that they increase inequities between the rich and the poor. That is, these economic measures do not solve social problems, they increase them.

Protesters also point to the systemic corruption mafia which has impoverished Ecuador. Credit: Ivan Castaneira (2019)

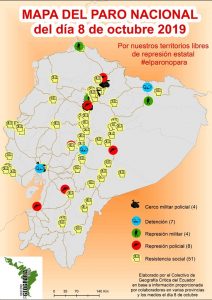

Map of the October 8 national strike showing areas of resistance and repression. Credit: Critical Geography Collective of Ecuador

The following text is a repost of an open letter to the mayor of Barcelona, Ada Colau, setting out a manifesto for a reorganisation of the city in response to COVID-19. The manifesto currently has over 1600 signatures. Visit the manifesto website for more details and to add your signature: manifiesto.perspectivasanomalas.org/en The COVID19 pandemic and the experience of confinement h...

The holidays are special; a chance to stop working, slow down and spend time with family and friends. The numerous family gatherings will likely involve discussions about the state of the world, politics, climate change, and maybe even degrowth. In case you find yourself in this scenario, we have put together this list of tips and suggestions for how to discuss degrowth with family and friends...

For the third year in a row, the Degrowth Summer School is being held on the Climate Camp in the Rhineland. It runs from the 18th to 23rd of August. Just 10 days before the start of the Summer School the foundation „Stiftung Umwelt und Entwicklung Nordrhein-Westfalen“ has cancelled our funding. The reason they‘ve given us: The Summer School takes place too close to actions of civil disobedience...