This post is part of a mini series on which The Himalaya Collective collaborates with degrowth.info. Together, we aim to forge connections between individuals and groups striving to achieve alternative economic and social systems both locally and globally, and to highlight real-life practices inspirational to the degrowth movement. You may read this post on the Himalaya Collective’s website, in English, or in Hindi. You may also read the other pieces of the series here.

Kashmir, June 1: Among the towering Himalayan ranges in Kashmir, nestled within valleys shaped by time and snow, lives a community whose rhythm is not governed by clocks or calendars, but by the land itself. These are the nomads of Kashmir, people whose lives revolve around migration, livestock, tradition, and an enduring bond with nature. Semi-nomadic communities, such as the Gujjars, follow seasonal migration patterns, whereas nomadic groups like the Bakerwals remain in constant motion and rarely settle in one place for long. The Gujjars, typically undertake a single annual migration during the peak summer months, moving to a specific high-altitude location. They do not live in one place for long, nor do they lay permanent roots in the soil they walk upon, seeking new pastures for their animals, as their ancestors did for centuries.

In the Chattergul Mountains of Kashmir, part of the majestic Harmukh range in Kangan block of Ganderbal district, this life plays out year after year. The region is not just stunning in its beauty, with glacier-fed rivers, lush alpine pastures, and herb-laden forests, but it is also a harsh and unforgiving landscape. Heavy snowfall, sudden storms, and bitter winters test both the land and its people. But these mountains are home. The nomads, especially the Gujjars and Bakarwals, have developed an intimate relationship with the land, understanding its moods, its offerings, and its limits.

Abdul Qayoom, a seasonal teacher, said migration typically begins in April, timed with the growth of fresh grass in the higher reaches. The decision is not spontaneous. It is rooted in routine, instinct, and environmental cues passed down through generations. Men often leave early morning to seek work in nearby towns, earning daily wages to support their families. Women, on the other hand, shoulder the bulk of the journey herding livestock, managing household duties, and caring for children. They don’t need to decide where to go, the routes are set in memory as they migrate to the same location every year. Yet the journey is anything but easy. With no proper roads and few modern amenities, families begin their trek at midnight to avoid scorching heat and traffic mess whileguiding horses carry their essential belongings across rugged terrain.

Despite the nostalgia often associated with mountain life, the reality is far more complex. Climate change has made traditional knowledge harder to rely on. Snowfall, once predictable, now melts sooner, affecting water availability in grazing areas. Less snowfall has increasingly disrupted nomadic life by affecting grazing, water sources and resource management. Climate change, driven by rising temperatures and altered atmospheric patterns, is a key cause. Water scarcity has become a significant challenge for the community, forcing them to reroute traditional paths and adapt in ways that are both mentally and physically demanding. Migration, already a difficult task, is growing more uncertain each year.

But the road ahead remains uncertain. The impact of climate change is not just environmental but existential. In Gulmarg, one of Kashmir’s iconic tourist destinations, the lack of snow has already impacted the winter economy, leading to broader economic disruptions. For nomads, whose lives depend entirely on the health of ecosystems, the risks are far greater. Earlier snowmelt, irregular rainfall, shrinking grazing lands, and reduced access to water all threaten a way of life that has endured for generations.

Farooq Ahmad, a Gujjar, explained, Change is inevitable. Traditional attire is slowly giving way to modern clothing. Livestock rearing, the backbone of our livelihood, is witnessing a decline. The younger generation is increasingly seeking education and alternative employment, often drawn to towns and cities for opportunities different to pastoral life. Yet for all the change, there remains a strong emotional connection to this way of living, one shaped by harmony with nature, by the dignity of hard work, and by the stories etched into every trail.

He further said, ‘’The resilience of our communities is nothing short of remarkable. Our lives are rooted in socialisation, in a sense of shared purpose and collective survival. While we don’t celebrate festivals markedly different from the settled Kashmiri community, the way they live, the values they carry, and the culture we protect are distinct and deeply rooted. Our homes, mud and clay huts built with layered insulation, are designed to provide warmth in winter and cooling in summer. As we migrate to high altitudes, we rely on these huts for comfort and protection, since we lack modern cooling devices. Even during heavy rainfall or western disturbances, they provide much-needed warmth and shelter throughout our seasonal journey. Some of our people hold knowledge of herbs, weather, livestock, and land management that is unparalleled. It is passed not through books, but through conversations during evening times, through songs, and lived experience.’’

Tanveer Ahmad Khatana, another seasonal teacher talks about the education system of nomads. Access to education and healthcare continues to be a major challenge. To bridge the education gap, the Directorate of Samagra Shiksha in Jammu and Kashmir has taken significant steps for our children. During the summer migration period, it operates 1,723 Seasonal Centres across the highland pastures of the union territory. These schools, active from May to October, are a beacon of hope for nearly 33,819 children of nomadic families. These teachers, known as seasonal teachers, accompany nomadic families to the higher reaches of the Himalayas, offering education to these nomadic children.

In classrooms pitched on grasslands and taught under open skies, children learn the alphabet while their parents tend sheep and goats nearby. These schools do more than educate, they preserve the possibility of a future where the community’s identity can coexist with selected aspects of modernity. These schools are known as seasonal schools because they function only during the migration period of the nomads.

A community member, Farooq Ahmad from Chatteragul Kangan shared, that while opportunities in education, employment, and infrastructure are steadily increasing, there is also a growing concern about the erosion of core values, languages, customs, and landscapes that define their identity. Many feel social pressure to migrate to urban areas or pursue conventional careers, often leading to a disconnect from their cultural roots. He mentioned his personal choice to preserve at least one essential part of their heritage, their language, despite the challenges.

Among the younger generation, particularly those involved in academic institutions, there is often a preference for a balanced path. They support adaptive conservation, which involves integrating selected modern tools like mobile connectivity and access to healthcare to improve quality of life, while also working to sustain traditional grazing practices, indigenous knowledge, and cultural heritage.

Shahnaz, a PHD scholar at the University of Kashmir from the Gujjar community, further talks about the adaptation that is already underway. Communities are adjusting migration routes, changing the timing of travel, and even altering the type of livestock they raise. Some are exploring alternative income sources such as wage labour, local trade, and educational advancement for their children. But these efforts need support, both from government institutions and civil society. Creating early warning systems for weather changes, protecting traditional grazing lands, improving access to water, and supporting sustainable pastoral practices can make a lasting difference. These communities are not just surviving, they are innovating within their means. But without structural support, resilience has its limits.

Shahnaz added, “Our community represents a unique blend of cultural practices and adaptability, navigating socioeconomic changes while preserving its traditional lifestyle, including our pastoralist and agricultural heritage. Our way of life teaches the world how to respect nature and how to keep it healthy and balanced. We live sustainably, drawing benefits from the environment without causing it harm.

We have now permanently settled in one place. However, some time ago, while working on a project related to the nomadic lifestyle, I spent a few days in the mountains with the nomadic community and spoke with them about their way of life during migration. They lead a very simple lifestyle, herding livestock and engaging in farming. Once they move to the high altitudes with their livestock, some of them start farming if they find suitable conditions, and some even do kitchen gardening. This allows them to continue living this way despite facing many challenges, such as climate change and identity crises. Still, their deep love for tradition, passed down through generations, and strong community ties keep them connected to this lifestyle.

My ancestors stopped migrating almost a century ago due to several reasons, including economic stability and modernisation. Given the current circumstances, this lifestyle may disappear in the future, depending on the choices of the younger generation.”

“What the nomads of Kashmir offer to the world is more than just a story of survival. It is a lesson in living with the land, not off it. It is about adapting without erasing who you are. It is about endurance, not just of people, but of culture, memory, and values in an increasingly volatile world. These Mountains and the families who journey through them remind us that tradition and progress do not have to stand at odds. They can, in fact, walk side by side, just like the herders and their animals do, year after year, along the mountain paths of Kashmir’’ she concluded.

The cultural sector has a crucial role to play in both imagining and enacting sustainable futures. In this article Neus Crous Costa explores the interlinkages between culture and the environment, and how the international movement Culture Declares Emergency aims to make a change.

At the end of the Degrowth Cabaret at the ISEE Degrowth Conference in Oslo, a handful of conference attendees started a backwards walk from Christiania, Oslo, to Christiania, Copenhagen. Degrowth.info talked to them to learn more about this peculiar feat.

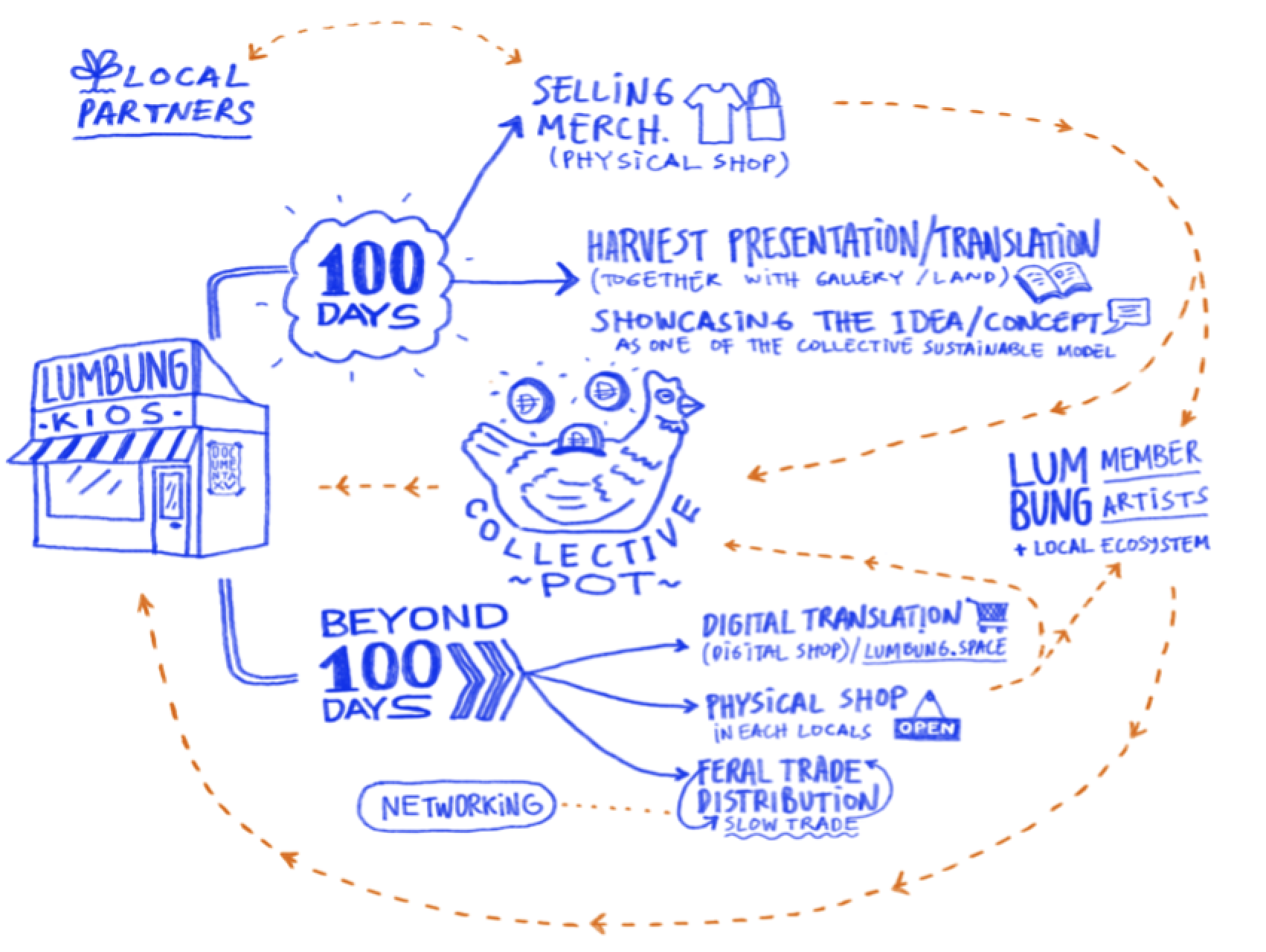

In 2022, art collectives and curators of documenta15 restructured the practice of producing and presenting art: away from classicism and economical individualism towards a culture of commoning knowledge, sufficiency and embodied community. Is documenta15 thus a degrowth art event? Yes, to some extent. The way it failed demonstrates an important lesson for the degrowth movement.