In November 2021, more than 4.5 million people voluntarily left their jobs in the US, the highest number since records began. Popularly known as the ‘Great Resignation’, the ongoing rejection of work-as-we-knew-it may not be a social movement in the normal sense of the term, but it is certainly a sign of rolling social upheaval. The increasing bargaining power of labour in the Covid economy, and an increasing unwillingness to risk life, liberty and happiness for precarity and a minimum wage, coincides with the rise of a newly vibrant anti-work movement. ‘Unemployment for all, not just the rich’, goes the slogan of the 1.6 million-strong Reddit community, r/Antiwork, which posts people’s stories of exploitation in – and subsequent liberation from – the workplace. China’s ‘lying flat’ movement is another instance of this, criticising the Chinese tech industry’s ‘996’ work pattern of 9am to 9pm, six days a week, and – with tongue-in-cheek – advocating for ‘lying flat’ as its philosophical movement.

Activists and scholars interested in degrowth have long considered freedom from the dictates of the capitalist workplace a core part of any viable degrowth future. From very different angles, two timely books were recently released which expertly delve into these issues, and are worth reading alongside one another.

Time, Labour and the Self

The subtitle of Four Thousand Weeks – ‘Time and How to Use It’ – might indicate that this is just the latest preachy instalment in the self-help genre to tell us how to maximise our output during our limited lifetime (which, as the title indicates, generally spans just 4000 weeks). On the contrary, it is rather concerned with fundamentally rethinking our productivist relationship with time, not wrestling back control over it.

In place of the neoliberal ‘grind culture’ approach of maximising productivity and taking on ‘side hustles’ which we might expect, Burkeman undertakes a philosophical exploration towards the acceptance of human finitude. This results in profound insights into the existential dead-end of modern Growthism: echoing Weber’s analysis of the Protestant work ethic, Burkeman notes that much of our drive for productivity stems from an angst regarding our finitude, and it is only by accepting the shortness of life, and the general insignificance we have in the larger fold of things, that we may stop striving so hard to be productive, to ‘make our mark’ or ‘leave our legacy’. Paradoxically, it may only be in the liberation from our self-importance and this mission of transcendence – that is, our acknowledgement of our ineluctable limits – that we may be able to start the project of co-constructing meaningful lives in the present. By giving up on the inner urge to produce, Burkeman points out, we can learn to slow down, cultivating some of the slower rhythms and rituals which degrowth activists have long practiced and advocated for. As the writer and philosopher Bayo Akomolafe exhorts, ‘The times are urgent; let us slow down.’

Given that it falls broadly into the genre of (anti-)self-help, this focus on the self might sound individualistic, apolitical, or selfish. Yet, this very acceptance and cultivation of limits is a thread which also runs through much of the most insightful work on degrowth. Burkeman is aware, of course, that our ability to negotiate with time is certainly structured by our social conditions – the self is social, as much as our sense of self can contribute to larger patterns. To create a healthier and less capitalist or productivist relationship with time, he highlights the key importance of collective rhythms of slowness. Drawing from the work of Terry Hartig, for instance, Burkeman notes that ‘what people need isn’t greater individual control over their schedules, but rather what he calls ‘the social regulation of time’’ (191). Studies, for instance, have shown how the more people are on holiday simultaneously, the happier a nation is likely to be. A collective holiday provides not just individual rest and time for families and friends to break bread together, they provide a collective pause, a social sigh of relief from the treadmill of the Machine economy. Far from demanding individualistic adaptation, this would indicate the need for a renewed focus not just on shortening the working week, but including other transitional demands like extended public holidays, festivals and the right to a statutory sabbatical.

Burkeman contrasts such collective idleness to the stifling overwork of contemporary surveillance capitalism, but also to early Soviet attempts to re-engineer the workweek and keep factories running every day of the year, without pause (called the nepreryvka). Under Stalin, workers were divided up into staggered four-day workweeks and would follow different calendars, with just one day off as a ‘weekend’. As one commentator notes, ‘With the weekend gone, labour became the framework around which people built their lives’. Rather than smoothly conforming people to the machine, however, resistance developed as people realised they could no longer relax collectively, with even spouses ending up on utterly mismatched shifts.

Similarly today, individualism and the market economy have ‘overwhelmed our traditional ways of organising time, meaning that the hours in which we rest, work and socialise are becoming ever more uncoordinated’ (199). In place of decelerationist social practices such as the siesta, for instance, we get accelerating gig work and on-demand scheduling. This, of course, has major implications for community organising and all forms of collective politics, as Burkeman describes:

‘All this comes with political implications…because grassroots politics – the world of meetings, rallies, protests and canvassing – are among the most important coordinated activities that a desynchronised population finds it difficult to get round to doing. The result is a vacuum of collective action, which gets filled by autocratic leaders, who thrive on the mass support of people who are otherwise disconnected – alienated from one another, stuck at home on the couch, a captive audience for televised propaganda.’ (200)

Ultimately, though, the quest for our time is not instrumental. Rather, just as the hobbyist will spend hours on something which to others will look frivolous or ‘unproductive’, this is about reclaiming time for its own sake, without shame: ‘In an age of instrumentalization, the hobbyist is subversive: he insists that some things are worth doing for themselves alone, despite offering no pay-offs in terms of productivity or profit.’ (158)

Against Accelerationism

Complementary themes are raised in a book which, unlike Burkeman’s, does explicitly and sympathetically mention degrowth, albeit in passing. Breaking Things at Work is a punchy, decelerationist Marxist book which brings to the fore the ongoing value of a Luddite analysis of technology. It advances ‘a politics of slowing down change, undermining technological progress, and limiting capital’s rapacity, while developing organization and cultivating militancy’ (127-128). While Luddism has long been misunderstood as a general animosity to all technology (whatever that would actually mean), Mueller rightly emphasises that Luddism – true to its original sense – actually implies a collective politics which questions the capitalist application of technology.

Technology has been overwhelmingly used in the context of capitalism to disenfranchise, disempower and exploit, and workers and communities must engage with technology critically if any common space of liberation is to be carved out. As Kranzberg’s famous first law of technology states, ‘technology is neither good nor bad; nor is it neutral.’ It thus becomes almost fruitless to discuss automation in the abstract: automating tasks does not liberate workers and lead inexorably to greater freedom from the workplace, but instead it is used to redistribute labour, deepen exploitation and further polarise society in favour of profit.

Mueller’s nuanced analysis brings Luddite politics right into the 21st century, following a historical thread starting with Ned Ludd in early industrial England, and leading us through 20th century debates around automation, right up to contemporary struggles against (variously) Big Tech and planned obsolescence, and for a ‘right to repair’. Noting commonalities with his project, Mueller asserts that ‘degrowth shares with Luddism an acknowledgement that liberation is not tied up with endless accumulation of capital, and, further, that well-being cannot be reduced to economic statistics’ (132).

Alignment with the degrowth corpus continues in his critiques of productivist radicals (such as the Fully Automated Luxury Communists), writing that, ‘instead of imagining a world without work that will never come to pass, we should examine the ways historical struggles posited an alternative relation to work and liberation, where control over the labour process leads to greater control over other social processes, and where the ends of work are human enrichment rather than abstract productivity’ (29).

While Mueller’s distaste for slow lifestyle politics or ‘ethics’ might indicate some antipathy with Burkeman’s focus on the existential relationship with time, ultimately they come to a largely common understanding of the challenges facing social life under an accelerationist capitalism which profits from dragging us apart. Returning to the Great Resignation mentioned at the opening of this piece, it is clear that deep discontent with work, production and our relationship to our own finite time have never been more relevant. The search for autonomy(-in-common) is the yearning many of us feel after decades of neoliberal assault, and these books provide two important signposts on the path to that liberation.

In his writings on the ‘iron cage’, Max Weber described ‘the tremendous cosmos of the modern economic order…bound to the technical and economic conditions of machine production which to-day determine the lives of all the individuals who are born into this mechanism’. He speculated that this cosmos would underpin our lives ‘until the last ton of fossilized coal is burnt’. We know that we cannot allow that to happen – our coexistence on the planet cannot wait that long. But at the same time, we cannot rush and lose sight of what is important. We must lie flat too. Both of these books indicate ways that we might live with this key paradox.

While it is now largely clear what degrowth is striving for, how to realize the transformation towards this end state has not been engaged with satisfactorily. The Future is Degrowth (TFiD) and Degrowth & Strategy (D&S), two books that now complement the burgeoning popular literature on degrowth, set out to find answers to this underexplored question.

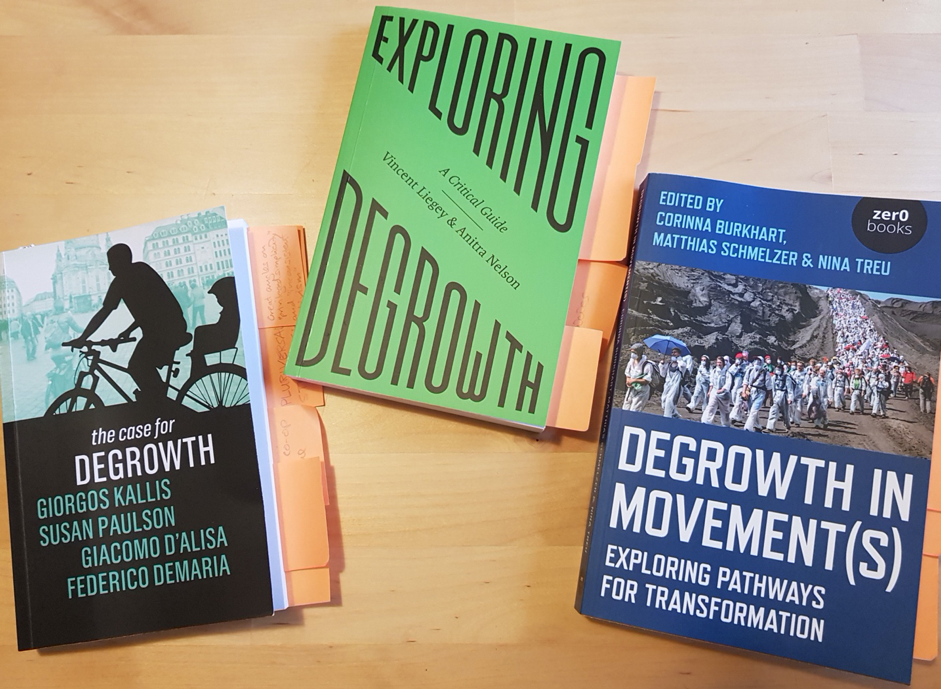

A year ago, in August 2020, we launched our jointly authored book Exploring Degrowth: A Critical Guide (Pluto Press). ‘The book you hold in your hands’ states Jason Hickel of the University of London and author of Less is More 2020, ‘paints a picture of the new economy that lies ahead — an economy that enables human flourishing for all within planetary boundaries.’ Discussion about degrowth has exploded since then when a cluster of general interest books on degrowth appeared in 2020.

Hickel succeeds once more in making a clear yet robust case for degrowth, providing an accessible introductory text that the movement has long required. Degrowthers may remember 2020 as the year their ideas entered the mainstream, or at least the edges of it. As the coronavirus pandemic has prompted a renewed societal conversation around alternative futures, discussions of degrowth are...