In the midst of the COVID-19 crisis, violence against women is increasing. More women are isolated at home with abusive partners and without resources and opportunities to leave. In Canada, where only a few months ago funding for Ontario rape crisis centres was slashed by $1 million, the political pressure to intervene in gendered violence has increased. Many women’s organizations, such as the Canadian Women’s Foundation, have noted the increased risk for violence during the pandemic. In response to some of these concerns, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau announced $40 million in funding to women’s shelters and sexual assault centres across the country. These interventions are important and lifesaving, and they speak to the long history of feminist organizing against domestic violence in Canada. However, if feminists in Canada are to counter violence against women in all its forms, now and after the current crisis, we must conceive of this violence as systemic rather than interpersonal – rooted in a global economic system that denies women sovereignty over their land as well as their bodies. The COVID-19 crisis comes on the heels of another disaster that disproportionately harms women but about which many feminists in Canada remain silent: the construction of the Coastal GasLink (CGL) pipeline through the unceded territory of the Wet’suwet’en Nation. As many Wet’suwet’en women have argued in their fight against the pipeline, there is a clear link between extractive projects and increased sexual violence against Indigenous women. The final report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls found, for instance, that the work camps – aptly described as “man camps” – established to construct and maintain extractive projects bring with them dramatic increases in rates of violence against Indigenous women in the neighbouring communities.

We must conceive of this violence as systemic rather than interpersonal – rooted in a global economic system that denies women sovereignty over their land as well as their bodies.Kyle Edwards, in an investigative piece for Maclean’s, details the harrowing experiences of eleven Indigenous women living near workers’ camps in northern Alberta and B.C., where some local health stations stock up on rape kits in advance of workers arriving. The women at the helm of the Wet’suwet’en resistance state in no uncertain terms that violence will increase as a result of the CGL pipeline too: the Unist’ot’en camp, spokesperson Freda Huson reminds us, is only 66 kilometres away from the “Highway of Tears,” on which dozens of Indigenous women have disappeared. That extractive projects increase violence against Indigenous women is an important, though under-recognized, reason for the fight against the CGL pipeline. As Carol Linnit observes in the Narwhal, B.C.’s environmental assessment of the pipeline neglected to account for its potential impact on Indigenous women and girls. Such negligence prompted, in part, Wet’suwet’en Hereditary Chiefs’ request for a judicial review of the assessment. Yet despite the clear links between sexual violence and resource extraction, settler feminists have largely refused to align ourselves with Indigenous women organizing against the pipeline. The movement to #shutdowncanada in February mobilized many climate activists and labour organizers in support of Indigenous sovereignty and against environmental devastation, but there has not been a similarly cogent response from mainstream feminist organizations. While influential and well-funded women’s organizations – such as the Canadian Women’s Foundation, the YWCA, and the National Council of Women – each take vocal stances against both domestic and sexual violence, none have explicitly lent their support to Wet’suwet’en women. In the midst of the pandemic and renewed concerns about violence against women, work on the CGL pipeline continues.

By remaining silent, settler feminists in Canada have risked both complicity in this violence and irrelevance in a women’s movement that is global in scope.Such silence is troubling. In separating the violence of resource extraction from struggles against domestic and sexual violence, Canadian settler feminists have disengaged from local and global movements that attack the systemic roots of violence against women. Indeed, resistance to the CGL pipeline is one of many Indigenous women’s movements across the world that remind us that extractive projects disproportionately and unequivocally harm women. Indigenous Maya Q’eqchi’ women in Guatemala, for instance, have led legal and grassroots fights against Canadian mining companies after 11 Maya Q’eqchi women were allegedly raped by security personnel associated with Vancouver-based Skye Resources in 2007. Two survivors of the attacks, Irma Yolanda Choc Cac and Angelica Choc, have since held Canadian mining companies to account through a series of lawsuits that highlight the links between resource extraction and human rights abuses. While distinct in its history and relation to the Canadian settler state, Wet’suwet’en women’s resistance to the CGL pipeline is part of a global movement against the violent nature of resource extraction. Such movements teach us that sexual and gendered violence are systemic rather than individual, the consequence of capitalism’s predations. By remaining silent, settler feminists in Canada have risked both complicity in this violence and irrelevance in a women’s movement that is global in scope. As the COVID-19 crisis has brought violence against women to the forefront of public consciousness, we must organize against all conditions that produce this violence – including the extractive projects that take place on Indigenous land. This piece was originally published in the briarpatch magazine. Degrowth.info was kindly given permission to republish.

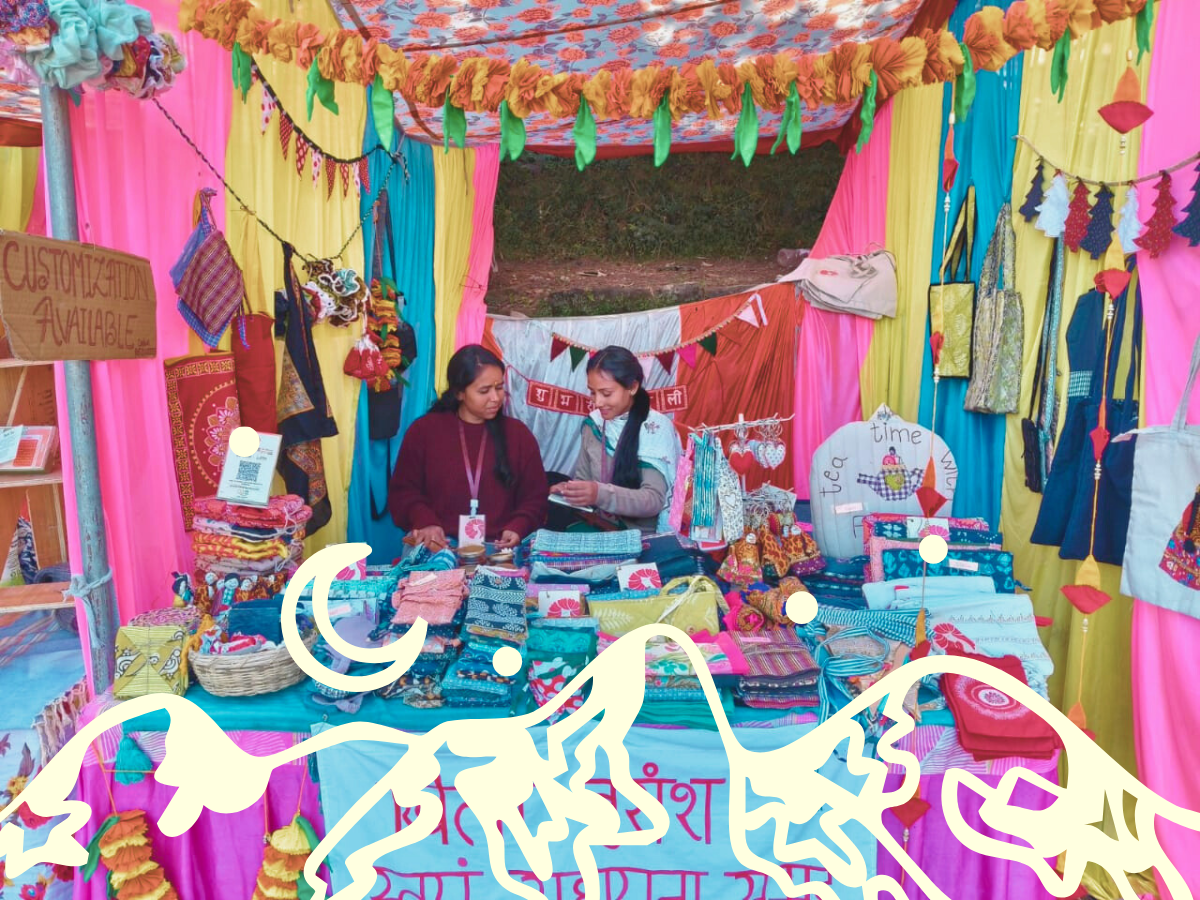

In this article, Shruthi documents the work of an empowering self-help group, Khili Buransh, in a remote Himalayan village in Uttarakhand, India. Shruthi explains how Khili Buransh leads a silent revolution against the prevailing capitalist-intensive, extractive, patriarchal, and casteist system.

Environmental activist, Francis Annagu, writes about the Boki women's fight against relentless timber extraction and wildlife trafficking in the forests of Cross River State, Nigeria.

Lázaro Mecha; as Chief of the Maje Embera Drua indigenous congress of Panama (on Maje Embera Drua), in the Bayano Region, which is currently organized by the indigenous congress (Maje Embera Drua indigenous congress): The history of indigenous communities dates back to when the Bayano Region was occupied, in past centuries, by the Embera, Unión Embera and Maje Cordillera peoples. The constr...