Despite an ever-increasing interest in degrowth scholarship, science, technology, and innovation (STI) have only been discussed marginally. Further, in some instances much thought on the topic has been marred by a certain romanticism envisioning a return to a technological past, or even technophobia. On the other side of the spectrum are many critics of degrowth who postulate that degrowth conceptualizations fail to account for the possibility of human ingenuity to develop new technologies that could save society while capitalism and growth continue in a sleek new green paint job.

We do not think it necessary to point out the flaws with returning to the stone age or renaissance for sustainability purposes. Neither should it be required to argue at length that the Elon Musks of this world will not save humanity with their hyper-technological capitalism. Rather, with this blog post, we make an appeal to the wider degrowth discourse and movement to further debate the role of technology and innovation in helping to achieve a sustainable degrowth society. It is vital to imagine different forms of science, technology, and innovation not bound by the persisting growth imaginary. Beyond this, a much more nuanced view of STI is also required.

We hope to make our case by sharing insights and reflections from our recent session at the STS (science, technology, and society) Conference Graz 2022. This annual conference is one of the key STS conferences in Europe seeking to bring together various perspectives on the interplay between science, technology, and society. To clarify, while STS and STI are closely related, the latter is a framing which considers specifically the interplay of science, technology, and innovation, which was the key interest of our session.

Our session focused on exploring different imaginaries around degrowth in connection to STI. We invited participants to submit contributions drawing on a plethora of imaginaries, to connect degrowth and STI in novel ways. We proposed these imaginaries could include, but were not limited to: convivial conceptualisations, responsible innovation and technology, open science, political ecology, gender studies, queer theories, post-coloniality, and crip-perspectives. The aim was to present various imaginaries and discuss them in a participatory setting. Through the presentations, various themes emerged. Some of which have already found relatively more attention within degrowth, such as conviviality, feminist perspectives, and counter-hegemony.

Other themes have only briefly been mentioned previously within degrowth, such as, queer theory, crip-perspectives, innovation resistance, as well as mega-projects. Notably, these less discussed topics in degrowth have found relatively more attention in STS in recent years. After the presentations we invited all presenters and session participants into a debate, to share STI imaginaries in connection to degrowth, and pose questions for scholars to consider moving forward. In the following, we present a snapshot of questions and themes that emerged which seem highly relevant for degrowth to engage with. Importantly, we recognise that these are our interpretations and observations from this session. In no way do we claim to have achieved an unbiased analysis.

As stated above, a more nuanced engagement with innovation and technology seems prudent within the degrowth movement. Our session highlighted the need to question, oppose, and overcome the persisting socially perceived purposes of innovation as having to create profits, and open the door to imagine different innovation and technology which fulfils societal needs. This in turn raised the ever-pressing discussion of how to define societal needs. From this, the need emerged to debate the role that innovations and technologies could and should have in achieving a degrowth or postgrowth society. Relevant in this context also became questions on megaprojects as well as existing infrastructures that are not compatible in their current usage with degrowth principles. In other words, what technologies and innovations fit a degrowth transition and do these include new and/or old infrastructures?

What is clear is that a demonisation of technology and innovation lacks nuance and is unhelpful, but questions of their purpose and role in a sustainable degrowth society as well as the path towards it are needed. One of the presentations focused on knowledge production in autonomous zones, posing questions of what might constitute non-material innovation. Does innovation always mean something new, and does it have to be material-based? And what are the connections to maintaining, repairing, and re-discovering existing and/or non-material interpretations of innovations?

Such queries were also picked up by multiple other presenters who highlighted various approaches to imagine and conceptualise STI. A presentation on crip-perspectives- the applying of disability justice lenses - in the context of degrowth highlighted the very need for technology and innovation that enables accessibility and supports peoples’ livelihoods. This is inherently aligned with conviviality principles, but so far, such perspectives are lacking in the degrowth discourse. Examples of material-based innovation (e.g. 3D printing of accessibility kits) but also non-material innovations were proposed e.g. crip-time (theory). Crip-time asks to rethink the connections between time, visibility, and marginalisation. Essentially exploring how time can be differently experienced by people with disabilities, as well as rethinking histories and futures around disabilities.

A different, but connected, presentation highlighted the need for queering data for degrowth and how inputs from those marginalised spaces can further push degrowth imaginaries beyond binaries, normal/abnormality and (un)conformity. The discussion highlighted the need to proliferate feminist, queer, crip and post-colonial perspectives in order to push the boundaries of degrowth imaginaries of technology and innovation and offer a wider plethora of approaches to imagine sustainable societies.

Overall, the role of STI requires much further debate within the degrowth movement. It is clear that degrowth neither represents a return to the stone age, nor can it fetishize technological solutions to the climate crisis. Through the above, we hope to help a much-needed emerging debate around STI in degrowth scholarship to gain traction, and to help trigger more nuanced understandings on technology and innovation for degrowth.

At the Post-growth Innovation Lab at the University of Vigo we have started to discuss and research much of the above and hope for increasing engagement with the topic(s) in the future. The signs for this look good. As we write, we are on the way back from another conference (European Society for Ecological Economics 2022 in Pisa) where many ecological economics and degrowth scholars showed a keen interest in the aforementioned topics and debates.

We owe a massive thank you to our presenters (Helena Fornstedt, Hannah Duffew, Scott Leatham, and Dan Durrant) and all the session participants in Graz.

A growing alliance of tech billionaires is accelerating the political trend towards authoritarianism. Not because they hate voting in principle, but because genuine democracy might impose limits: on wealth, on extraction, on the fantasy of endless growth. Read more about tech authoritarianism and the fight for 2026 in this piece.

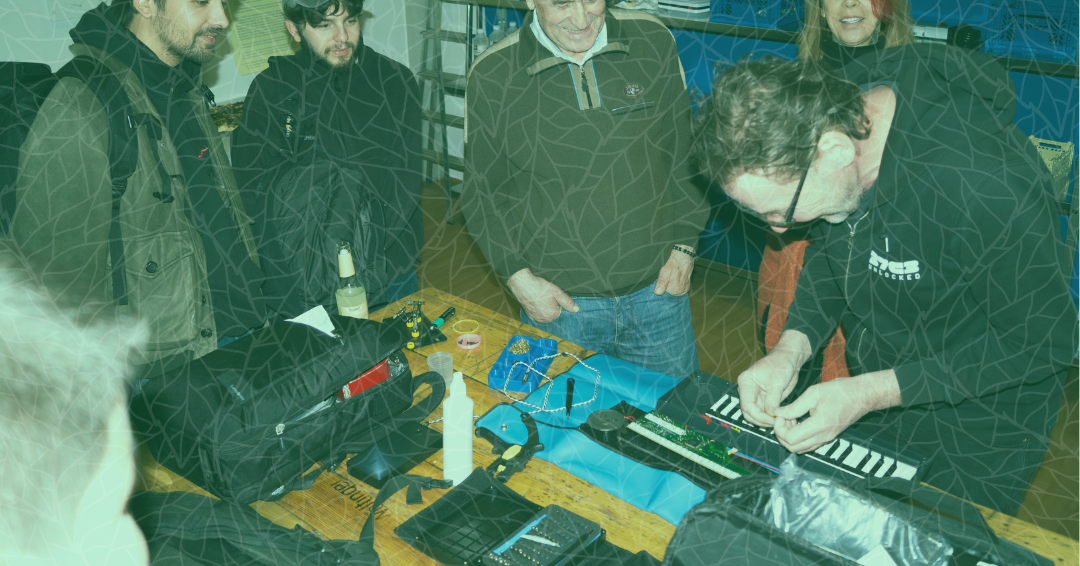

Kreisler, a space of community repair and share in Berlin that offers a hands-on response to the crises of overconsumption, social isolation, and infrastructural neglect.

'The State of Carbon Dioxide Removal' report, published in January 2023, was presented as ‘a first-of-its kind, independent, scientific assessment.’ Rather than questioning the quite genuine commitment of scientists and researchers working to address climate change, the Myth of Sisyphus highlights a fundamental problem with the ontology of sustainability Science itself