Disclaimers: Nobody should feel guilty for not being vegan. We live in a system that makes it incredibly easy to eat animal products, and there are numerous reasons why people may need to do so. Furthermore, I think animal rights are important, but I also think it is important to situate these kinds of discussions within the current conjuncture. It is now over two years since Israel begin committing genocide in Gaza, aided and abetted by most western governments. This must remain a focus for us all until Palestine is free. Finally, this blog post makes reference to (anti-)colonialism. I still have a lot to learn and unlearn in this area, so I will undoubtedly sometimes get things wrong. Please get in touch if you think I’ve missed the mark, and I will gladly take comments on board.

Degrowth and veganism are two ideas which aim to build a more just and sustainable world. Yet, surprisingly little attention has been paid to the synergies and potential alliances between them. I argue that degrowth and veganism share many of the same principles. I also argue that either one taken without the other is inherently contradictory. I propose points of learning that each movement can take from the other, as well as from elsewhere.

Degrowth is a systemic critique of an expansionist, individualist, capitalist economic system based on exploitation, unequal exchange and unsustainable levels of production and consumption. Degrowth posits that capitalism and its drive for the endless accumulation of wealth are fundamentally incompatible with ecological stability and social equity. Degrowth scholars propose shifting to an alternative paradigm, where productive capacities are instead geared towards meeting the needs of human population without breaching planetary boundaries.

Veganism is a critique of the notion of human supremacy, and the systems of thinking and acting that lead to some forms of life being reduced to a commodity, and subordinated to the satisfaction of human taste preferences. Defining veganism (or indeed any …ism) is always inherently a normative exercise which carries significant baggage, but according to The Vegan Society, veganism is “a philosophy and way of living which seeks to exclude—as far as is possible and practicable—all forms of exploitation of, and cruelty to, animals”.

Although the core idea of degrowth – that we should reduce excessive production and consumption, especially in ecologically damaging and socially destructive industries – is globally applicable, in practice it applies mainly to wealthy nations in the global north who are overwhelmingly responsible for this overproduction and overconsumption. This piece, and its discussions of veganism, are aimed at those same people. I am categorically not addressing the camel herder in Tunisia, the Bedouin in Palestine, or the indigenous people living on lands stolen from them in countless western nations when I talk about veganism, because their impact is dwarfed by that of wealthy people in wealthy nations. The problem is industrial livestock farming. I am instead appealing to people like me – people who have the time, access to food, good health, and economic security to campaign for structural changes to the food production system (and make changes to our own behaviour). I am also not advocating for immediate, universal and absolute abstention from the consumption of animal products, as Drew Pendergrass and Troy Vettese do in Half-Earth Socialism. In this world, some people need to eat and/or produce meat.

Degrowth and veganism have plenty in common. Both movements call into question the status quo, and criticise systems that are made possible through exploitative relationships with our fellow beings and the wider ecosystem. Both stand in opposition to powerful economic and political interests, resulting in frequent misrepresentation and concerted efforts to delegitimise and paint proponents as extremists. Both also force us to wrangle with our own learned beliefs, and confront uncomfortable contradictions between our behaviour and our morals, in particular our sense of what, how much, or indeed who, we are entitled to consume. It is no surprise that veganism is far more common among ‘degrowthers’ than among the general population.

Veganism is, I argue, a natural and necessary component of degrowth, just as degrowth is a natural and necessary component of socialism. Degrowth, and left-wing political projects more generally, are usually rooted in values such as compassion, justice, and autonomy. As Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara once said, “the true revolutionary is guided by great feelings of love”. We know that animals have the capacity to form relationships with others and to feel joy, but also to feel fear and pain. It is not controversial to suggest that animals are thus worthy of some moral consideration. It is therefore logical, for those of us who are privileged enough, to extend these values to animals as well as to our fellow humans, especially when the only cost to us of doing so is settling for a different lunch.

For the degrowth movement, this would mean devoting more time and effort, in our work, activism, and personal choices, to dismantling the current food system, which is based on domination, subordination and violence – values that are antithetical to those we are guided by. Not only would this reduce our inner moral inconsistency, but it would also go some way to achieving ecological goals, with industrial animal agriculture being one of the main contributors to ecological breakdown (although this is not the primary goal of veganism).

The animal agriculture industry is also one of the worst offenders when it comes to the abuse and exploitation of humans. A disproportionately large percentage of slaughterhouse and factory farm workers are from marginalised communities, and suffer from unsafe and exploitative working conditions, resulting in dramatically higher rates of mental illness and workplace injury. A true utopia is one in which all humans and non-humans live free from exploitation. That should be our goal as degrowthers. If the ‘all’ in ‘A good life for all within planetary boundaries’ only refers to human beings, and we still exploit and slaughter trillions of animals every year, we will not be living by the values on which degrowth is built.

Veganism, in turn, has a lot to learn from degrowth. For example, the focus of veganism must be on the food system as a whole, itself embedded within the capitalist economic system. Veganism as merely an individual lifestyle choice is futile. In my opinion, disrupting the production and distribution of animal products is far more important than convincing one more person to switch to oat milk. What is produced is consumed, and what is produced is determined by powerful institutions that work together to uphold violent and oppressive industries because they are profitable. That is what we need to change. Having said that, acknowledging the systemic nature of a problem does not absolve us from all personal responsibility to act in accordance with the vision of the future we wish to see.

Vegan capitalism, in which we all switch from buying chocolate bars made by Nestle and burgers made by McDonalds to buying vegan chocolate bars made by Nestle and vegan burgers made by McDonalds, is not a desirable outcome. These corporations actively undermine the values I discussed previously. Degrowth is good at focussing on structural change, and it is structural change that the food system needs. The rise of vegan alternatives in a capitalist system is purely a profit-seeking and greenwashing exercise by corporations who have no interest in animal rights or social justice. For example, Vivera, a brand of vegan meat substitutes in the UK, is owned by JBS, who are the world’s biggest meat producer, responsible for the slaughter of millions of animals every single day and illegal deforestation in Brazil.

As Marx noted, technological innovations are not neutral but are summoned into being in a specific form, by specific people, for a specific set of purposes. Degrowthers are distrustful of techno-optimism for this reason. The same is true of veganism. We cannot let veganism be summoned into being in a colonial and extractive form, by capitalists, to increase their profits. We need degrowth veganism – veganism that is awake to ecological limits and the intersectional nature of capitalist exploitation.

Veganism and degrowth both have the potential to help overthrow colonial relations. Indeed, a central pillar of degrowth is to end the imperial extraction of resources in the global south, by the global north. Veganism, too, “offers an opportunity to disrupt colonial logic by challenging the most basic building blocks of colonialism, which reduce life forms to mere objects for capitalist exploitation”. Indeed, modern human-animal relations (i.e. industrial large-scale and factory farming) were only made possible through the historic and ongoing dispossession of indigenous lands by settler-colonialists, and the enclosure of common land in Europe. And it is these relations that allow us, the wealthy masses of the global north, to go to the supermarket and buy animal products, produced at great cost, often in the global south, to the environment, people, and of course animals.

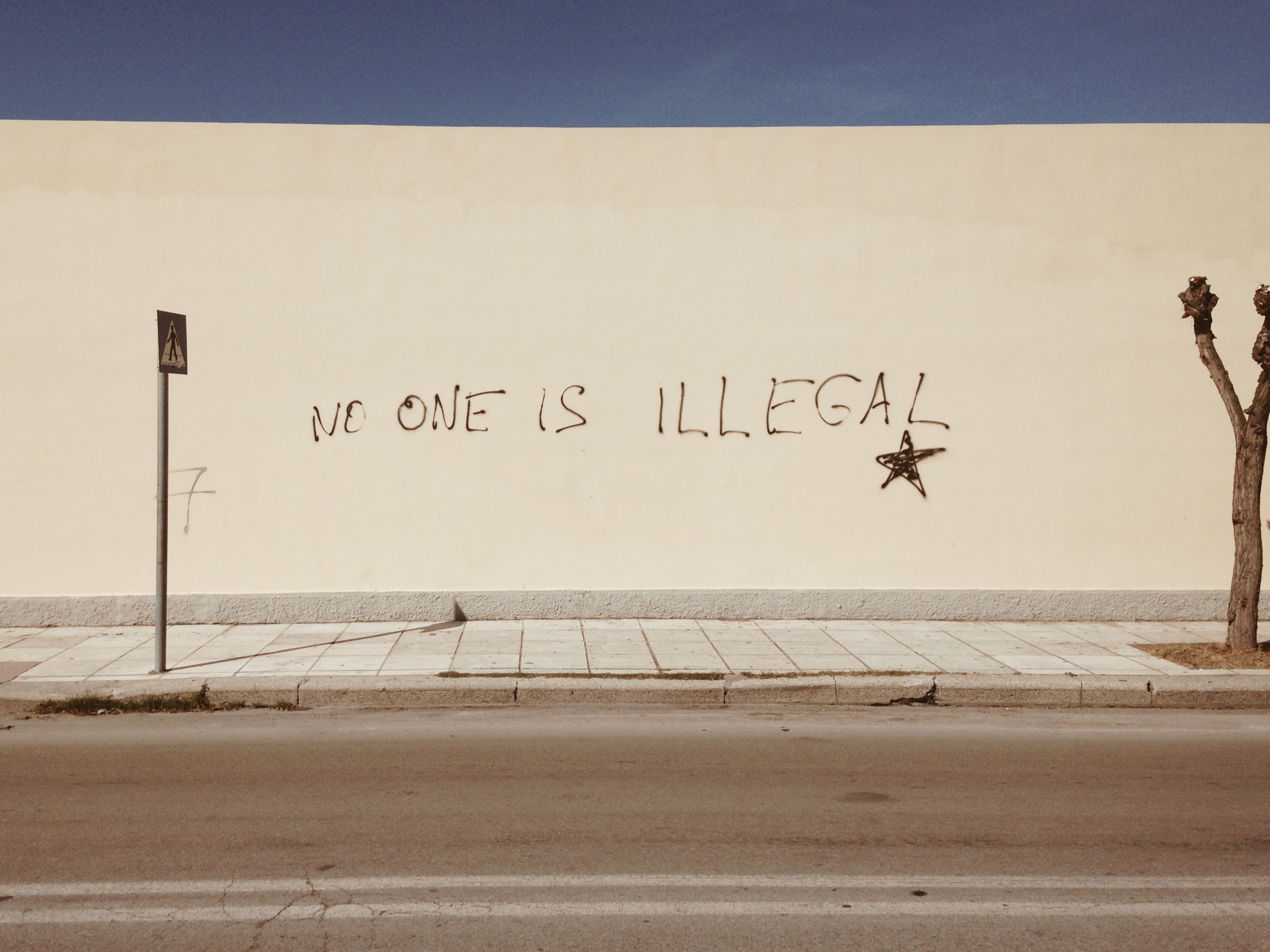

The anti-colonial potential of both movements is not a given. We must be extremely careful to avoid naively prescribing and enforcing solutions based on our own privilege. My current understanding is that, for degrowth, this means amplifying and joining those calling for debt cancellation and reparations and supporting the sovereignty of countries in the global south, enabling them to break from extractive relationships with imperialist powers in the north. For veganism, it means respecting indigenous cultures and their historically successful stewardship of the natural world (which also means an end to privileged individuals disingenuously invoking indigenous cultures to avoid confronting their own choices), and building a justice-centred movement that focusses on accessibility and systemic change over shaming and guilting individuals, forms alliances to dismantle systemic oppression wherever it occurs, and amplifies marginalized voices.

As degrowthers, we should recognise that commodifying life itself and subjecting animals, and our fellow humans, to unimaginable suffering, at great cost to the Earth, is inconsistent with our aims. We need to act in accordance with our values, and put food system revolution at the forefront of our agenda. As vegans, we need to ensure that the struggle for animal liberation is not an isolated fight, but rather embedded within broader anti-capitalist, anti-patriarchal, and anti-colonial struggles.

Veganism and degrowth are both key components of any kind of positive vision of the future. They are two sides of the same struggle, because workers and animals are both victims of capitalist exploitation. It was industrial slaughter that inspired Henry Ford’s vision of industrial capitalism. When capitalists promised workers ‘a chicken in every pot’, they were never referring to wage increases, but rather artificially cheap meat. Animal life was the frontier that allowed capitalists to continue extracting surplus value from their workers.

As Dick Gregory put it: “the same thing that we do to animals, the system is doing to us”.

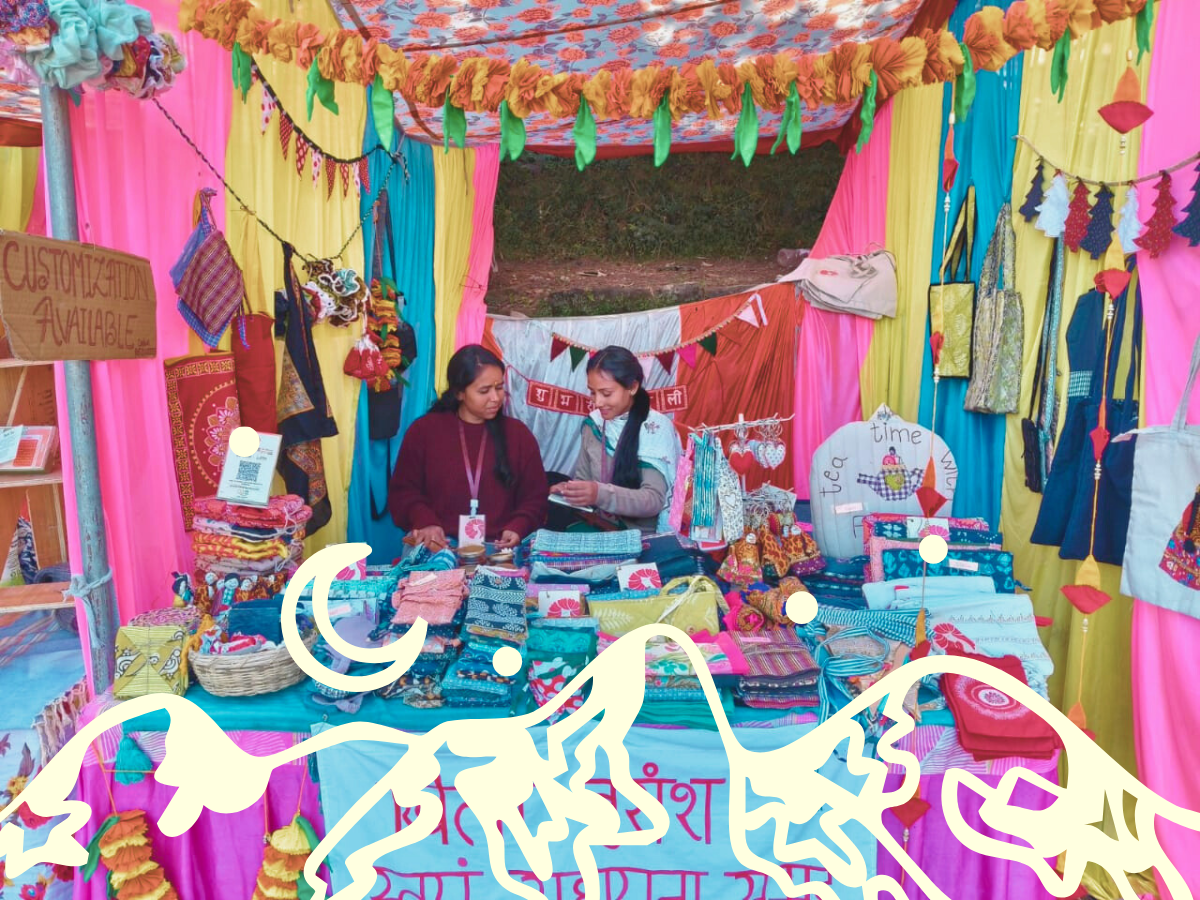

In this article, Shruthi documents the work of an empowering self-help group, Khili Buransh, in a remote Himalayan village in Uttarakhand, India. Shruthi explains how Khili Buransh leads a silent revolution against the prevailing capitalist-intensive, extractive, patriarchal, and casteist system.

In degrowth, we often speak about how the relationship between the Global South and the Global North could look differently. But what happens at the edges, and how can we understand these edges or points of encounter in the degrowth discourse?

Reconciling degrowth and law isn’t always easy, given the anarchist underpinnings and anti-statist leanings of some in the degrowth community. One vision of a degrowth world is of decentralized, autonomous, convivial communities of people in tune with their supporting ecosystems, consuming no more than they need, sharing as much as possible and treating each other with compassion, fairness and mutual respect. No central state power, no police, no borders, no masters and servants, no conspicuous consumption, no oppression. This, however, doesn’t necessarily require a world without law, just a world with law that is much different from the forms of law that prevail in today’s rapacious and unjust world.