Degrowth is more than just an academic discipline. It is a convivial movement with care at its centre, based on values such as solidarity and justice, and on a commitment to transforming the world in a way that respects people and nature. Yet like all communities, degrowth consists of people. People are complex, messy, and cannot be the perfect embodiment of the values of the collective they belong to. People do not always agree with each other. Where people exist, conflicts arise, harm becomes a potential, and healing a necessity. Furthermore, the degrowth movement operates in a capitalist and imperialist system where power is allocated unequally. As the degrowth movement grows, so does its vulnerability to visible and invisible power dynamics. While the degrowth movement is not immune to these, we can collectively change how we want to navigate conflicts, harm, and unequal power dynamics. This article reflects on the different ways the degrowth movement can respond to harm and engage with conflicts in a way that recognizes, breaks and heals unhealthy patterns.

Different definitions of conflict cohabit in the literature; for the sake of this article, we define conflict as incompatible positions coupled with a lack of trust or hostile feelings. While differences of opinions can sometimes create tension, feel unpleasant, and require us to spend extra time on coming up with a solution, disagreeing is a natural phenomenon that arises from the diversity of perspectives existing in a group or a society. This doesn’t necessarily lead to conflict, and is not to be avoided. However, if we don’t trust that others are willing to help us meet our needs or take our well-being, our concerns and our valid objections seriously, relationships become strained and conflictual feelings can arise. Conflicts – especially if unaddressed – often lead to harm, and it is important to find ways of engaging with conflict that are neither violent, nor try to silence either party.

Abuse is an act that, conscientiously or not, causes harm, injury, distress, endangers someone’s life, or restrains someone’s rights. It can take many forms (physical, emotional, sexual, organizational, discriminatory, financial, and neglect…) and can be visible or subtle and hidden. Although anyone can be affected by a situation of abuse, the likelihood of being a victim of abuse increases for people in vulnerable positions (for example because of age, disability, power, gender, cultural background…).

We understand harm as any injury, pain, or loss felt by an individual or community, regardless of its cause and the intentionality thereof. When a person or community experiences harm, their ability to meet their needs and their overall well-being is usually negatively impacted.

As authors of this piece, we have all witnessed, or have been made aware of, cases of academic mentorship abuse, as well as verbal, physical, and sexual abuse happening in the degrowth movement. This includes cases between members of the movement, irrespective of where the harm occurs, because even conflicts and abuses taking place outside of explicit degrowth spaces, such as conferences or a local degrowth group, will have repercussions on degrowth spheres, and therefore should be of concern to the movement. In some cases, harm has taken a collective dimension, in that it affects all or most people belonging to a group. There are a few important contextual aspects that can increase the likelihood and impact of harm, which we need to be careful of if we want to heal these cases, and prevent further ones from occurring:

How do we respond to this as a movement? What can degrowthers do to prevent harm from occurring, and to address it when it does occur? What we suggest below is by no means a textbook solution or a cure, but rather some ideas and suggestions to spark reflection and initiate change.

We won’t ever produce a healthier environment for degrowth if we don’t acknowledge current dysfunctions. However, identifying problematic structures and cases of harm can be challenging in the degrowth movement, because we tend not to expect such harms to occur in our spheres, as they are so distant from our ideals of conviviality, care, justice and respect. In a movement with such strong ideals, there is also an unease to speak up for fear of repercussions. The power of one influential individual, or the consequences of speaking up against abuse, are heightened in a small movement; since due to the limited number of degrowth organisations there might not be another group with whom to collaborate on one’s topic of interest. Moreover, the degrowth movement remains a loose entity, with no formal structures of care and no institutions to transform conflicts. All of these factors contribute to turning the issue of harm into a systematic one. Harm is therefore silenced, individuals can be deeply hurt, isolated and disillusioned, and the movement becomes prone to structural abuses.

The section above attempts to cast light on this by outlining some of the ways in which harm has occurred, and occurs, within the degrowth community. We encourage everyone in the degrowth movement to go further and look critically at their particular community, for example, by asking some of the following questions:

A transformation away from structural harm would require unlearning our sexist, racist and hierarchical biases, seriously considering our positionality in the degrowth movement and the consequences it may have, and actively reflecting on how to address these consequences.

But in a system where we constantly experience harm first hand - both in our ‘everyday’ world and in the degrowth world - we unconsciously learn precisely what we want to unlearn. The unlearning process is therefore no easy one, and we need to accept all the support we can get, be it from theorists or practitioners, from the degrowth movement or beyond. Most importantly, we need the strong commitment of all members of the degrowth movement to move in this direction.

This effort could be materialised in various forms: the degrowth movement can support research on this unlearning process, by giving it visibility, or by dedicating some of their own research time and financial resources to it; degrowthers can reach out for help, attend workshops and trainings, and strive to put learnings into practice in their daily lives and work; and finally researchers and practitioners interested in unlearning processes can spread their work and engage in knowledge sharing, whether they belong to the degrowth movement or not. Degrowth conferences could be a platform for such sharing, but other tools and formats such as social media, webinars, retreats etc. could also be used.

The above suggestions should enhance the environment in which we work and make occurrences of harm less likely. But, as already stated, harm does and will occur whatever we do to prevent it, and the degrowth movement, being a loose assemblage of various actors, lacks a formal structure or institution within which to process this harm. In this context, what should we do to offer justice to people who have suffered harm? We suggest that the degrowth movement draws inspiration from other movements to rethink its dealing with harm and conflicts.

The most common form of justice in Western societies is a punitive justice: one in which sanctions, exclusions and imprisonments are considered fair and necessary. It is beyond the scope of this article to enter the debate of the implications, pros and cons of this deep-rooted punitive ideology; but a large range of types of justice exists. We’d like to think beyond punitive justice into types that may be more in line with the degrowth movement.

Transformative justice comes from the understanding that in order to stop harm we must address “the underlying dynamics that created conditions for harm to happen in the first place”. It seeks not just to transform the person identified as having the most responsibility for the harm, but to transform the community and context in which the harm occurred. This doesn’t diminish accountability, but increases it by encouraging everyone to ask, “how may we have contributed, are we contributing, or are we part of these systems that create the harm that we're trying to address?”. We celebrate that the degrowth movement is starting to explore this.

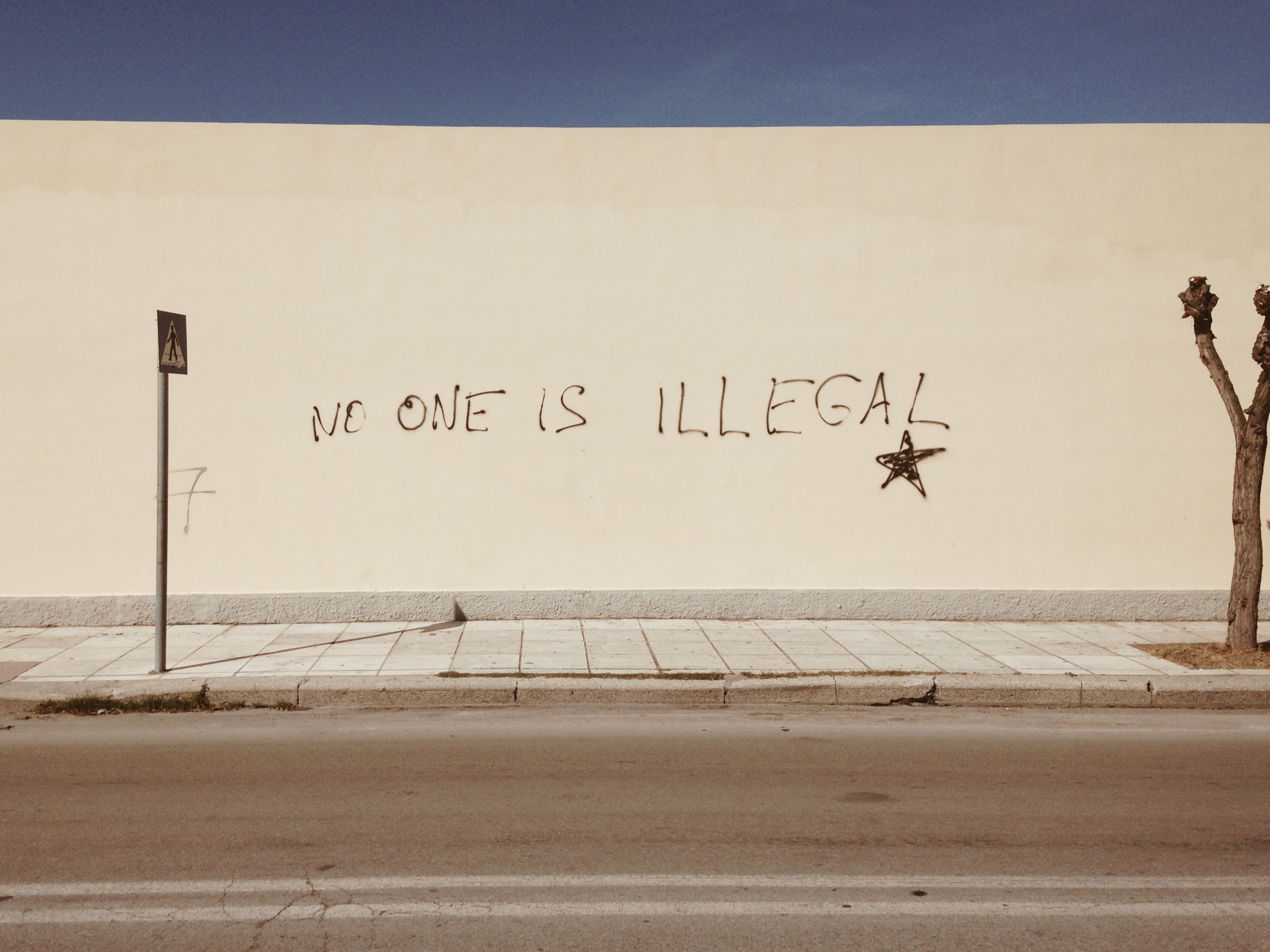

The degrowth movement can also draw inspiration from literature on community accountability, which is a process for addressing harm within a community, without relying on external authorities. Much aligned with the values of transformative justice, it suggests that communities work on things such as: affirming values and practices that resist abuse; developing specific strategies to address and transform harmful behaviours; practising communication skills; and providing safety and collective support to those experiencing harm. Some communities that have systemically experienced oppression and for whom punitive justice has historically been a synonym of persecution (such as indigenous communities, communities of people of colour, immigrant communities, poor and low-income communities, people with disabilities, sex workers, queer and trans communities) have created their own systems of justice through transformative justice and community accountability. The degrowth movement can learn a lot from these communities, bearing in mind that these concepts should be adapted to each context.

Nonviolent communication (NVC), a tool frequently used in activist movements, is based on the idea that people cause harm to each other because they lack the capacity to meet their needs in a way that works for everyone. NVC seeks to address harm by using a variety of communication tools (e.g. using “I” statements, making requests rather than demands, sharing non-judgemental observations, etc.) that help navigate disagreements in the workplace. NVC in particular connects with degrowth because both are based on an understanding that we all share a wide range of needs (e.g. food, shelter, autonomy, connection to others, etc.) and both desire to develop systems to meet those needs for the benefit of everyone’s well-being. This “orientation to needs” can help those in the degrowth movement adopt a communication style that reflects their political philosophy.

What would these structures of care, these alternative types of justice and conflict resolution look like in the context of the degrowth movement? How would they interact with existing bodies, such as university committees, or even courts of justice? There are a multitude of answers to this question, and we need a collective search for the best options. While it might be desirable to have centralised training programmes to equip organisations to deal with harm, we should encourage a plurality of models, based on a plurality of contexts, and inspired by the experiences of other movements. Conflict prevention and transformation must be localised, with each degrowth group or institution developing their own ways to address conflict and harm as fitting to the context and circumstances. The level of transparency must be appropriate to the conflict, such that it prevents conflicts of interests, unnecessary public exposure of involved parties, and unconstructive shaming.

It is not for us to speculate what such degrowth conflict transformation systems should look like. Forums organized at degrowth conferences or the International Degrowth Network would be much more suitable platform to have such conversations and make recommendations. But considering our knowledge of conflicts in the degrowth movement, we loudly advocate for all degrowth institutions and groups to investigate the topic seriously, create space for reflection and feedback, and collectively develop toolkits to deal with harm.

The degrowth.info collective would like to thank Noémie Cadiou, Mario Díaz Muños, KC Legacion, Joëlle Saey-Volckrick, Anne Sheridan and Olzhas Toleutay for their collaboration in writing this piece.

Democratic Confederalism in North-East Syria is threatened. Resisting centralisation efforts by the new Syrian government and keeping women on the revolution front is the way forward for any prosperous and ecological alternative system.

In degrowth, we often speak about how the relationship between the Global South and the Global North could look differently. But what happens at the edges, and how can we understand these edges or points of encounter in the degrowth discourse?

Democratic confederalism, the ideological framework organizing society in Rojava, outlines the features of a post-revolutionary justice system. Hundreds of thousands of protesters have taken to the streets across the United States and beyond in response to the police killing of George Floyd. Protesters in Minneapolis, New York, Los Angeles and dozens of other cities demanding justice were me...