Capitalism is prevalent as an economic system, and an ideology of progress at the cost of human exploitation and environmental destruction. Its relationship with every aspect of human life has been critically examined in disciplines like political ecology, economics, sociology, anthropology, humanities, social sciences, art, urban studies, and so on. Such scholarship delineates how capitalism has (re)produced inequalities and injustices in discursive and coercive forms.

In the last decades, scholarship on degrowth, as an antithesis to capitalism, has grown in volume. To a certain extent, it has made an impression among activists and researchers in Europe as a way to achieve a just and sustainable society. Capitalism poses significant challenges to society in multiple ways, such as climate crisis, structural violence, environmental degradation, deforestation, etc., which have social, political, and economic consequences, particularly for people living on the margins of the global economic system. Degrowth entails transforming society to become more climate-resilient, moving beyond structural violence, dismantling power hierarchies, and pursuing global equity, decolonization, and peace. It is essentially a transformative paradigm shift to disrupt capitalist modernity.

This article argues however that degrowth as a critique of capitalism cannot alone solve problems of modern society across the Global North and the Global South. Degrowth needs to be developed at multiple levels through an inclusive policy framework, where citizens' participation is crucial in order to push towards the construction of a degrowth society.

The Global North has achieved a significant level of economic growth and development, and its population does not face extreme poverty compared to the Global South. The 1990s can be seen as an era of economic liberalization in the Global South, and in India and China in particular, with the World Bank denoting such countries as ‘new globalizers’. Since this liberalization in the Global South, the implementation of growth-oriented economic policies has exacerbated uneven wealth distribution in countries like India, Pakistan, and China, creating a considerable income gap between the rich and poor. An outcome of the growing economy in the Global South has been the creation of many millionaires, while at the same time, it has pushed millions of people into the trap of poverty. The supposed ‘trickle-down’ effect of a capitalist economy has been minuscule, and growth has not brought prosperity for all people.

Of course, policymakers are not oblivious to the fact that they follow a top-down approach to the design of welfare and social policies to address inequalities. While citizens may be able to choose between better or worse candidates, it is only through active public participation and deliberation in policymaking that the issues of the most vulnerable sections of society are likely to be addressed. On the contrary, the current situation is that policymaking is generally maneuvered by those who already have significant representation and authority in seats of power.

A feminist degrowth approach proposes an incremental, emancipatory decommodification and communization of care beyond the public/private divide as a strategy to achieve justice in care work. Every policy should be designed to keep critical aspects of class, gender, social origin, and other kinds of exclusion in mind. It has been often observed that social groups who are in a minority or victims of social hierarchy are left behind in the process of policy designing and agenda-setting. In a nutshell, the power to set the agenda for policymaking is a crucial factor, and so the incorporation of degrowth ideas in policy formulation will require addressing the issue of hierarchies in governance.

Crucially, degrowth must be adopted in practice. The indigenous visions of Buen Vivir/Sumak Kawsay, other alternative ideologies, have gained some success in this regard, having informed official discourse and policy in a few Latin American countries and the United Nations Environment Programme. Degrowth is not therefore the sole alternative to capitalism. According to the environmental activist and scholar Ashish Kothari, radical ecological democracy (RED) or ecoswaraj has the potential to counter the hegemony of growth-oriented policies and achieve socio-ecological transformation to a just society.

Amid the pandemic, the global economic situation has also reached a crisis, and the Global South has faced multiple challenges due to dilapidated health infrastructures and shortages of medical supplies, which have raised the death toll greatly. The wealthy countries of the imperial core, such as the UK, have also faced significant impacts of Covid-19. Moreover, countries like the US and Italy have seen thousands of deaths in the first and second pandemic phases despite having substantial health infrastructures. Capitalist societies profoundly failed to manage the pandemic crisis situation and to save millions of lives. It is undoubtedly true that pandemic has raised significant questions around the current economic system and given us a chance to rethink the future of humanity. The capitalist way of living must be rethought by world leaders and those at the forefront of policymaking across the world. However, it is unlikely that the small conglomerate of people who control the power to make policies will agree with degrowth.

Degrowth may not be a silver bullet to the world's problems in general, and in Global South in particular. However, as the Global South seeks to mitigate structural inequalities, spatial injustices, climate-induced poverty, and caste-induced injustices, it ought to become subject to examination how degrowth can be incorporated into policymaking and discourses of (post)development.

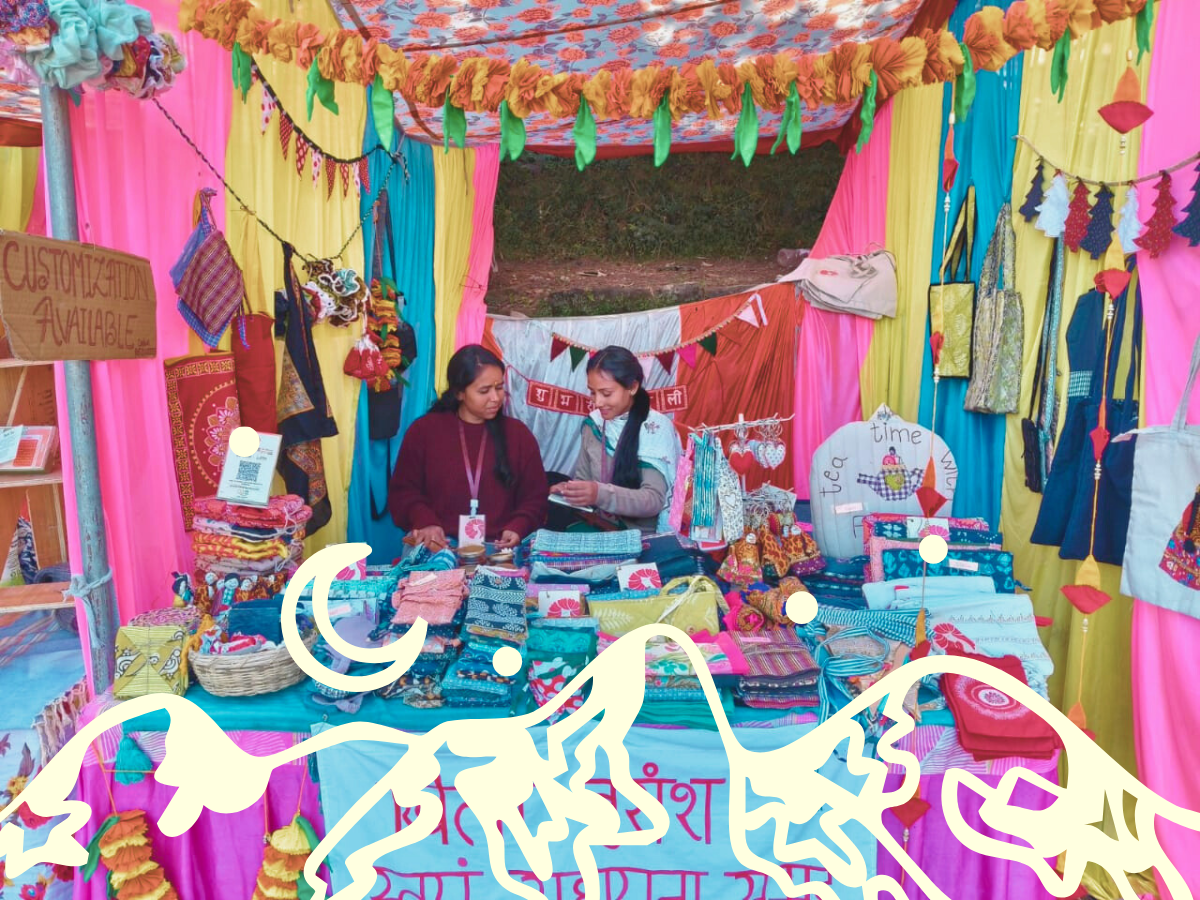

In this article, Shruthi documents the work of an empowering self-help group, Khili Buransh, in a remote Himalayan village in Uttarakhand, India. Shruthi explains how Khili Buransh leads a silent revolution against the prevailing capitalist-intensive, extractive, patriarchal, and casteist system.

Walk Peace EU's marches for justice gather people together to walk across country borders and connect. This invitation to 'walk the talk' prompts us to question whether we live what we preach, then act on the insights gained during the walk.

In the midst of the COVID-19 crisis, violence against women is increasing. More women are isolated at home with abusive partners and without resources and opportunities to leave. In Canada, where only a few months ago funding for Ontario rape crisis centres was slashed by $1 million, the political pressure to intervene in gendered violence has increased. Many women’s organizations, such as the ...