By Bernard Herry Priyono

Grand Indonesia is a gigantic shopping mall at the heart of Jakarta, the capital of Indonesia. Across its gate is Plaza Indonesia, another luxury shopping destination for the country’s elite and middle classes. The malls’ isles are always lined with sleek Italian sports cars, German premium BMW and Mercedes-Benz or grand British-made Bentleys. Thirty-five years ago the area was known to be civic spaces where citizens held political rallies. How in a matter of three decades these civic spaces were turned into commercial ones is a story that adorns business executives’ meetings in search of market expansion for their products among the Indonesian consumer classes.

A similar trend has been taking place across Southeast Asia: from Bangkok to Ho Chi Minh City to Kuala Lumpur. Indeed, this lifestyle transformation is part of the third wave of economic development in East Asia. The first wave occurred in Japan during the pre-war era, the second in South Korea, Taiwan and Singapore in the 1960s and 1970s, and the third during the 1980s and 1990s. How did it happen?

At the heart of it is the creation of a new breed of middle classes as the consumer class. It was the feat of economic liberalisation in the 1980s and 1990s that unleashed global financial transactions and made it easier for global banks and investors to enter untapped markets in the region.

This is how the transformation in the 1980s was depicted by Daniel Lev, an observer of the Indonesian politics: “As the old status was blown away by the new status supplied and fed by money, new recruits flooded the professions – from the civilian bureaucracy, from army, from upwardly mobile petty commercial and well-off peasant circles, as well as from aristocratic families for whom high finance, corporate board and the professional haut monde seemed sensible substitutes for the increasingly declassed government service”. This in turn created a new lifestyle aspiration commensurate to the middle-class jobs, education, income and status.

From the 1980s onward, the images of success have been widely defined in terms of business-centred jobs: young business professionals dressed in brand suits, driving luxury cars and dining out in posh Italian or Japanese restaurants. A new definition of lifestyle was born, revolving around a standard consumption package of suburban houses, cars, refrigerators, washing machines, TV sets, latest communication gadgets and well-known brands of packaged food, clothing and cosmetics. But, how big is this consumer class?

Of 252.8 million of Indonesian population in 2014, about 74 million are counted as middle classes and affluent consumers. The number is estimated to rise to 141 million by 2020. But there is a semantic trick, as the standard is set very low. International agencies like the Asian Development Bank and business consultancies define the middle class as those who live on US$ 2-20 per person per day. This is very comical, for there are about 80 percent of Indonesia’s population, or about 201 million, live on less than US$ 4 per day. Half of this number subsists on less than US$ 2 per day, still abjectly poor by any standard. Only 18 percent (some 45 million) of Indonesians live on between $4 and $20 a day. It is this social category that starts to acquire some of the trappings considered as the middle class.

Why this trick? First, the so-called middle class here has less to do with the notion of a political force called the bourgeoisie in the history of Europe than with a consumer group. Second, “the middle-class hype” is heralded by the business sector in a bid to expand consumer markets. That is why consulting firms are quick in broadcasting that Indonesia is “vast business opportunities that lie in the huge demands of the middle class; enterprises should focus on this particular class of people as none can afford to lose these costumers”.

Indeed, this class is ever hungry to grab everything in sight and stuff its insatiable maws with consumer goods. The business sector celebrates it, the government rejoices in it. The latest Indonesia Economic Forum held on November 25, 2014, for instance, had “The Rise of the Consumer Class” as its watchword. The opening speech given by Vice-President of Indonesia was ebullient: “The middle classes in Indonesia are fast increasing and this makes the country an investment destination. Our middle classes are the biggest in the region, and this makes Indonesia the biggest market in Southeast Asia”.

It is in this surge of lifestyle aspiration that a cult of economic growth is boosted further through the rage of extracting more, selling more and buying more. Not only have urban and rural landscapes been transformed haphazardly, but Indonesia’s rich natural resources are also being exploited more heedlessly. The entry point may be the aspiration of the middle classes, but they emulate that of the affluent. The lifestyle of these middle groups is then what the very poor crave to emulate.

The whole web of this consuming pathos in turn has brought into being a new-rich mentality: avaricious, predatory and insatiable. The city of Jakarta, for instance, is congested by regular traffic gridlocks; 70 percent of the city’s pollution is caused by motor vehicle emissions. While roads have expanded at only 0.01 percent, the number of motorized vehicles grew between 9 and 11 percent per year over the past five years. With the need for 20.7 million trips every day, it is utterly stupefying that 98 percent of vehicles on the road are private vehicles, serving 49.7 percent of trips, while public transportation fleets make up only 2 percent of vehicles but serve 50.3 percent of trips.

All this is what haunted me whenever I visited Europe in the past few years. I lived in London for six years in the second half of the 1990s, during which I regularly visited several countries on the continent. Concern for sustainable lifestyle was in the offing then but not as strikingly as today. The throng of bicycles that was negligible in the 1990s has now become part of urban landscapes. I have also learned that cooperative-based car sharing has gradually become part of lifestyle among the professionals in Germany.

It is heartening to learn that a new approach to lifestyle begins to be cultivated and perhaps has become an idiom within the policy circles. The growing vigour of ecological movements pursued by various groups within the green and de-growth networks may also be what is needed at the present historical moments.

Yet it is always thorny to answer questions as to how parallel movements can make entry into countries like Indonesia. There is something peculiar about the reigning herd mentality. Indeed, the way development is being conducted in Indonesia has always pitted the economy against the ecology, so much so that the idea of decoupling ecological impacts from economic growth is unthinkable. This is what makes it sound far-fetched to think of an economy that is ecological, as much as an ecology that is economical.

Why far-fetched? The problem lies not in ignorance but in something much deeper, of which lifestyle aspiration is part. At the heart of it is what is called uneven capitalist development. It refers to different historical trajectories at which capitalism arrives and works as a shaping force in different societies.

The type of capitalism that shaped European societies starting from the eighteenth century may not be the same as the one arriving in newly independent nations in the mid-twentieth century. But it must be conceded that capitalism became a new societal force in the latter only recently. Capitalism arrived as a full-blown societal force in Indonesia only in the 1980s, barely a generation ago.

Not only does the difference in trajectories create dissimilarity in the way capitalism shapes societies but it also creates divergences in lifestyle aspiration. Most Indonesians experienced this profound transformation of aspiration brought about by capitalism only recently. It involves a rapid aspirational climb from, say, having a bicycle to riding motor bike, then to driving economical vehicles in the scramble to owning premium and luxury or sports cars. That is why Indonesia has become the largest car market in Southeast Asia. BMW Group, for instance, has recorded between 25-35 percent of yearly growth in sales in Indonesia for the past 5 years. This is also true for many other car makers.

Here lies the irony. What starts to be abandoned or relinquished in the old capitalist economies may just begin to be avidly desired in the new capitalist economies. The fact that in a globalised economy companies can easily exit from the old capitalist countries and relocate their production houses and markets to these emerging economies ensures that what is seen as moribund in the former is exactly the source of consumer exuberance in the latter.

For the green and de-growth crusaders, this reality check is poignant. Any hope may have to take the form of another irony. The so-called middle classes in these developing countries are known to be enthusiastic emulators of almost anything European, American or Japanese. I imagine that if the ecological crusaders raise their banners and succeed in making the ecological lifestyle integral to the cultural standard in the advanced countries, perhaps the middle classes in countries like Indonesia would follow suit.

Even if only because they feel that going ecological and green is cool. -------------------- Bernard Herry Priyono teaches Social Sciences and Philosophy at the Driyarkara School of Philosophy in Jakarta

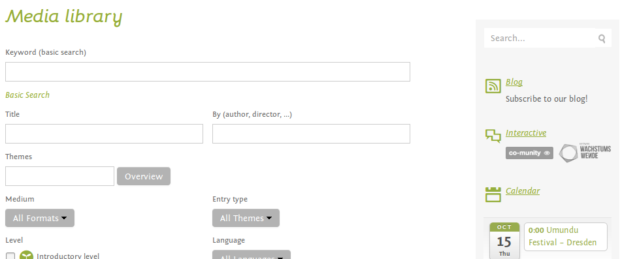

After almost a year of tireless work we are proud to present our degrowth library. Here you can find various materials related to the transition to an economy independent from economic growth. The library already contains almost 700 entries, from introductory videos to newspaper articles and scientific publications in different languages. Diverse search options and an extensive list of themes m...

… and the contribution of the "Degrowth in Action – Climate Justice Summer School 2015" By Elena Hofferberth With the 21st Conference of the Parties taking place at the end of this year, the United Nations climate process is heading towards another climax. The aim is nothing less than the adoption of an international legally binding agreement limiting atmospheric warming to a maximum of 2 deg...

Interview with Christine Bauhardt Prof. Dr. Christine Bauhardt is professor for Gender and Globalization at the Humboldt University in Berlin. Her main research interests are society-nature-relations and gender relations, feminist critique of the economy as well as migration and urban development. She took the time to answer our questions for the interview-series of the Stream towards Degro...