Europe is exhausted. It is exhausted after long years of what is labeled as the Eurozone crisis. It is exhausted after years of economic success and – now – prolonged years of political failure. Every single attempt of deepening the political union of Europe after the enactment of the Maastricht Treaty in 1993 and the introduction of the common currency that followed in 1999, failed in consecutive referendums. Remember Ireland 2001 with the Nice Treaty, remember the Netherlands and France in 2005 with the European constitution. This elitist concept of Europe was too much rooted in an overtly rationalist model of economic necessities. But humans are more than economic machines doing what markets expect and require from them.

At the same time, the European Union still remains the largest economic entity in the global economy. The continent is also still unrivaled in terms of the economic and social welfare that it provides to its citizens. But these two core distinctions are pretty much it. Of course, there are the beautiful old towns and picturesque cities, the natural grandeur of Europe’s diverse landscapes, its rich cultural and historic heritage. It is a museum for the entire world to remind everyone of a great past. Quite oddly, the name “Europe” and its association with a certain way of life is a rather recent invention. The European idea of an ever-greater union – based on liberty, democracy, social welfare for its citizens, a common market and free borders – is merely 60 years old.

For Europe, Francis Fukuyama’s famous notion of the “End of History” appears to look more and more appropriate. Today’s European’s, Friedrich Nietzsches “Last Men” (and Women), appear to be exhausted. In one way or another, this exhaustion bears down heavily on Europe’s cultural psyche. The very idea of Europe, its self-description and culture rests on being a project for humanity’s progress – including all its failures, perversions and dark sides. That means, its arc is that of a steady evolution, sometimes the revolution of ideas, as well as new concepts of how the world should be organized.

Pankaj Mishra noted that this longing for grand ideas is in fact an odd European habit. But when the West has been won, where to go now? When all horizons have been met, what next? What do you do, when you feel hollow down to your psychological and cultural core? With this continental version of the end of history, Europe lost its soul. When we talk of Europe today, there is no spark. There are no great feelings of hope, no weight of history felt on our shoulders. Not like in the immediate aftermath of the last War, when “Europe” finally promised the end of all borders, the end of all wars. Then, “Europe” was all about the future. Today, “Europe” is about EFSF, ESM, ECB, OMT and, of course, the famous banana regulation. This is the situation for Europe now.

The call of Giorgio Agamben in Libération in March 2013 for installing a Latin Union in Europe as some form of counter-power against the overweight of Northern Europe – well, let us be clear and blunt about that: Germanic Europe – was based on one very strong argument. That argument was that people live on the basis of their cultures. That is why living actually means to have a lifestyle. And that this lifestyle is informed, infused, held together by the history of people´s local cultural landscapes. For Agamben as a man from the Midi, from Latin Europe, the cultural landscape is the Mediterranean and all that for which it stands, the children of the olive tree. But even if you are from Germanic Europe as myself, you cannot help but commemorate the loss of something significant, something deep within yourself. German writers Thea Dorn and Richard Wagner – no, not the 19th century opera composer – titled their recent book “Die Deutsche Seele” – “The German Soul” and picked up the notion of culture and need for history that Agamben drew from his Latin perspective.

But some advocate that there is still room for Europe’s future by once again igniting its glorious past, its adherence to rationality and enlightenment – and a good dose of technocratic, technology-oriented policy. The battle against climate change in the form of a “Green New Deal”, based on “Green Growth” and investments into green technologies and renewable energy could form a new project for progress in Europe, as former Irish president Mary Robinson and Archbishop Desmond Tutu pointed out. In fact, it made it into the core strategies of the European Union for becoming the most innovative knowledge economy on the planet.

Of course, climate change and the greater ecological crisis we see unfolding today are the heritage of Europeanization, starting with the first shovel of coal into James Watt’s steam engine. So it would be only consequent for Europe to redeem its past sins by investing in green technologies, by setting up the right institutional framework with emissions trading, feed-in tariffs for renewables, by fostering green entrepreneurialism and rejuvenile itself. This is of course a prime example for an a-historic, means-oriented, culturally oblivious approach in our all-too European world. Will that quench the thirst for soul? For being woven into a rich cultural tapestry of 500 years? I would probably rather bet my money on the Eurovision Song Contest then!

The quintessence of this entire essay is this: No one lives on bread alone. If there is hope for the old continent, Europe needs an intellectual project that speaks to the heart and soul beyond 500 years of progress. This intellectual project might well be found in the unprecedented proliferation of grassroots movements responding to the dismantling of social and political arrangements following the momentous and ongoing financial crisis of 2008. Christina Flesher Fominaya and Laurence Cox managed to edit an insightful compendium “Understanding European Movements: New Social Movements, Global justice Strugges, anti-Austerity Protest” on this recent rise of bottom-up activism across the old continent. Common ground amongst all these different grassroots movements is to strongly question the results of the European project:

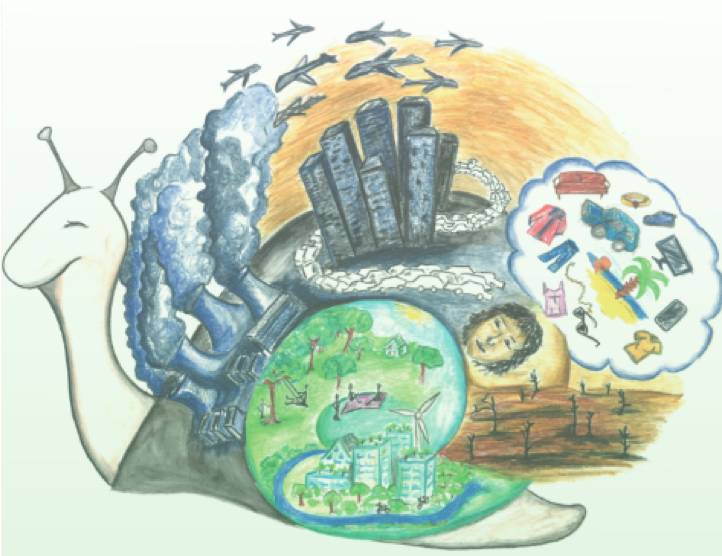

Above all, all these initiatives challenge the expansionist logic of the European project that moved us beyond every border, every horizon, every soul and now to the very limits of our planet and our existence.

What is probably most fascinating about all these movements is that they span the whole breadth and width of Europe, from East to West and, most notably, from North to South. Take for example the Transition Towns movement starting in Ireland and the UK, a dedicated grassroots, civil society activist idea of permaculture and local resilience whereas the Romanic battle cry for “décroissance” originated in France and took to the streets of Spain and Italy. But now, they are all over Europe, resonating deeply with people everywhere. Everywhere people come together in the sense of commonality, of collaboration, of local reference and global responsibility.

Show me something that has achieved that in the last 25 years, without any government intervention, without any initiative from Brussels! These movements bring in a breath of fresh air into this exhaustion that befell us Europeans and blocked any progressive idea of our own future, against the instrumentalist reasoning clouding our minds, against the end of history and the false heralds of “there is no alternative”. There is one: Postgrowth Europe.

Comment on this article on the German blog "Postwachstum"

André Reichel is Professor for Critical Management & Sustainable Development at the Karlshochschule International University in Karlsruhe, Germany and speaker at the Degrowth Conference

There’s lots of talk recently about the wealth of Jeff Bezos. There are maps comparing his wealth to entire countries, a “You are Jeff Bezos” game where you can spend his money on different things - like paying their fair-share of taxes, and a graphic that puts his wealth in perspective. A recurring point is that most people simply cannot fathom the amount of money he has. The number is $150...

Green growth advocates praise resource efficiency for its potential to incentivize the economy and lower its ecological impact. On the other hand, the Jevons Paradox, describes multiple situations (or rebound effects) in which increased efficiency leads to further consumption (either direct or indirect) which offsets the initial ecological benefits achieved. In this piece, I join this discussio...

Saturday 1st June 2019 marked a significant occasion for the degrowth movement: the inaugural ‘Global Degrowth Day’. Groups of people gathered together in places all around the world to engage with ideas of degrowth and alternatives to our growth-based society, guided by the event’s theme of ‘a good life for all’. The Global Degrowth Day was coordinated by the Activists and Practitioners int...