In Boki land, the roar of chainsaws is now the sound of cultural erasure. Over the last five decades, the forests of this ancestral area, situated in Cross River State, Nigeria, have endured relentless plunder through timber extraction, but also the trafficking of wildlife, with many species now endangered or already extinct. This destruction strikes at the heart of Boki women, who have for centuries sustained their families through traditional harvesting of bush mangoes, nuts, and vegetables. These forest gifts once served as living archives of wealth, identity, and intergenerational memory, but not anymore. Under the suffocating march of corporate extractivism, these Indigenous lifestyles are being replaced by the cold calculus of exploitation.

The destruction of Boki’s rainforests unfolds like a slow-motion crisis, one fueled by a web of entrenched interests. Timber cartels, often armed, operate with impunity. Alongside them, industrial-scale loggers such as the Chinese logging companies carve through the forests, leaving behind a scarred landscape where thriving ecosystems once stood. These actors are not rogue elements but function within a permissive system, shaped by weak environmental governance, global market demand, and the commodification of natural resources, that prioritizes profit over people. The consequences ripple far beyond felled trees. Deforestation here exacerbates global warming and deepens human insecurity; reminders that environmental harm knows no borders. For the Boki women, the loss is both immediate and intimate. Denied access to the forests that sustained their livelihoods, they can no longer gather wild nuts or cultivate crops without intimidation. Their exclusion from forest governance is rooted in long-standing gendered power relations and a history of top-down decision-making by government forest authorities, compounded by policies that fail to institutionalize women’s land rights, leaving Boki women without legal land titles and making it easier to ignore their rights. Their exclusion from decision-making highlights a painful irony: those most affected are often least heard.

Who, then, is responsible for the destruction of Boki’s ecosystem? Chinese logging companies, who carry out industrial-scale felling of timber for export, spearhead this destruction under the guise of "selective logging", a euphemism for the monstrous targeting of high-value trees like iroko and African cedar. These species, once pillars of the forest’s ecological and cultural architecture, are now corpses hauled away on trucks. What once sustained collective life for generations has now become a battleground, where pristine forests are traded under shadowy deals. What’s more, the government’s silence is deafening, while local authorities have been accused of being involved in illegal logging. The same system expected to fight forest destruction, is found culpable.

Since 2002, Nigeria has always been at the mercy of China. How? China has invested in infrastructure and lent funds to Nigeria, to fuel industrial growth and secure access to raw materials. Chinese-owned interests are fueling the felling of hardwood for export to China in a record 1.4 million logs. It has been uncovered how Chinese nationals forged land deeds with the help of corrupt local chiefs, erasing ancestral claims to customary land ownership with the stroke of a pen. Though the government retains the authority to acquire such land for public purposes under the Land Use Act of 1978, its customary tenure persists as an Indigenous and legal reality. This system stands in contrast to Western conceptions of land ownership, which are predominantly individualistic and exclusionary in nature. The loss in Boki is existential; an erasure of an entire people’s way of life. In the past, the Boki people across different villages have enjoyed peaceful co–existence and remarkable cultural harmony. Beginning on August 18 each year, the New Yam Festival gathers many farmers - both men and women - to thank the Boki god for a good harvest. Women cook Eru, Egusi and bitter leaf soups with leaves fetched from the forests, with dancing, drinking of palm wine, and the feeding of visitors. But this culture, which fostered bonds, unity, and communal sense, is no longer as vibrant or widely practiced as it was decades ago, before logging overshadowed the milieu.

Yet, amid this plunder of everything we know as ecological systems, the Banyinyi Boki Women’s Association has emerged not merely as nature’s protectors, but as architects of an alternative future. Rooted in a tradition where community and sustainability converge, the Boki women wove their resistance into something enduring. In 1959, the Banyinyi Women’s Association, a pan-sociocultural institution with the mandate to preserve Boki culture, was formed to encourage Boki women's sociocultural role in community development and the promotion of inter-village/clan cooperation. Over time, its responsibilities have widened, and today, the women’s association also plays a vital role in combating deforestation in the Boki rainforest.

On the frontlines of environmental defense, the women of the Banyinyi Boki association stage peaceful protests, a steadfast refusal to let their forests fall to complete destruction. Week after week, they gather, their very presence challenges both state and local authorities. But their resistance runs deeper than marches. In village squares and homesteads, they mobilize neighbors, building a grassroots network that demands tougher laws and real enforcement to shield Boki’s land. Their tools? Not just petitions - but persistence, solidarity, and strategy. Yet they know isolation is a losing strategy. They reach beyond their community, forging alliances with environmental NGOs. These partnerships become megaphones, amplifying their call against illegal logging until it echoes in halls of power far from their trees.

Unlike logging companies that see forests as commodities, Boki women understand them differently, as living systems: a reciprocal bond exists between the Boki women and the forest, rooted in respect, care, and interdependence, not extraction. The women’s resistance, rooted in reclaiming over 23,000 hectares of forestland decimated annually by corporate hunger, stages nothing short of a quiet revolution. From an ecocentric perspective, their struggle is part of a global reckoning, one that confronts authorities with the fatal flaws in modernity’s relationship with nature. Against the onslaught of extractive capitalism, the Banyinyi Boki Women's Association fosters sororal bonds and voluntary solidarity, standing in stark contrast to exploitation.

While some efforts focus on restoration, others confront destruction head-on. One of Banyinyi’s leaders and activists, Florence Kekong, embodies this spirit of reciprocal relationships with nature. In 2022, her reforestation project, where women planted bird’s eye pepper to attract seed-dispersing birds, became an act of ecological healing. "The birds are our partners," she explains. "They replant the forest for us." We can feel how this traditional knowledge, refined over generations, stands in stark contrasts to privately owned monoculture plantations that have degraded biodiversity.

The Banyinyi’s enforcement of state forest laws is equally innovative. When a Nigerian man was caught felling trees in 2020, the Boki women’s public shaming, parading him through the village with his confiscated chainsaw, was a performance of community justice. But could Chinese loggers face similar consequences? Unlikely. While local timber gangs operate under the threat of violence, the Chinese exploit something more insidious: the silent armor of state influence, secret deals with complicit chiefs, and the institutionalized impunity of systems built to shield power. For the Boki women, this imbalance isn’t just unjust - it’s paralyzing. How do you hold accountable an entity that exists beyond reach, protected by layers of state privilege?

More than an act of discipline, the Boki women’s shaming of the caught logger, exposed the absurdity of outdated environmental laws, where fines of one Naira (0.60 €) mock the gravity of punishment. "The law is a ghost," Florence remarked. "We are the real protectors." When confronting the chainsaw operator in 2020, they invoked a ritual - traditionally used to shame thieves - by tying forest vines around his waist while chanting: "You who cut the mother's limbs, shall wear her scars." Since state laws have failed Boki’s forests, this act of defiance exposes a deeper truth: the fight for environmental justice demands radical legal transformations, replacing exploitative systems with ecological law, rooted in interdependence and justice.

Like the Boki women defending forests, this vision rejects anthropocentric hierarchies, instead centering place-based governance and Indigenous wisdom. Their struggle forces us to ask: can we shift from exploiting nature to learning from it? The answer may determine not only the fate of their forest but also our collective future.

Maureen Osang, Public Relations Officer for Banyinyi Boki, explains the deep ecological knowledge passed down through generations of Boki women: “For centuries, Boki women have interacted closely with the forest because we’ve depended solely on organic foods. We had cocoyam grown on grasslands, a rich local bean called Otshe, and a special kind of melon known as Esambye that grows only in the forest. There are also many mushrooms we gather. In those days, women didn’t rely on meat like beef or cow - they thrived on local beans, Dawadawa, and mushrooms.”

This intimate relationship reflects a sustainable way of life. Boki women know how to harvest without damaging roots or overexploiting resources. They follow seasonal rhythms, leave parts of the forest fallow, and transmit this wisdom through daily practices and oral storytelling, sustaining a delicate balance between use and preservation.

In a conversation with His Royal Highness Ata Otu Fredalin Akandu, chief of Boki land, he echoed this connection to the forest’s abundance. “Our forests are full of wildlife, snails, for example. When women go to the farm, they pick snails along the way, left and right, and by the time they return, they may have ten snails to cook soup.”

Chief Akandu also described the forest’s vital ecological services: cold spring water for drinking, clean air, and rich biodiversity. “It’s in Boki that you find endangered species like gorillas, drill monkeys, and chimpanzees in the Afi mountains. They tell us that in all of West Africa, the only remaining rainforest is in the Cross River state - and especially in Boki.”

In this light, therefore, the ecological activism of the Boki women pushes back the environmental tragedy of sacrificing human-nature harmony for short-term gain.

If Indigenous knowledge holds answers, what stands in the way? Digging deeper reveals a provocative truth: perhaps our collective survival requires not just resistance, but a fundamental reimagining of power. After all, how can you negotiate with a system built to erase you from your ancestral land via forest annihilation? The Boki women know this. Their strength and collective well-being lie in shared vision, in resurrecting something that is, in fact, ancient: the sovereignty of collective care. When they shame loggers or replant bird-eye pepper to enlist birds as allies, they are resisting the destructive system while also giving rise to its replacement.

This is the true battleground. The struggle in Boki is not between development and conservation, but between two ways of being human: one that sees forests as warehouses of commodities, and another that recognizes them as kin. In this light, the women’s fruitful efforts are not stopgap measures. They are the first threads of a pluriversal future, where economies mirror ecosystems - regenerative, reciprocal, and rooted in place. As ecosystems collapse, communities and eco activists across the continent of Africa are advancing this shift - not as idealism, but as survival.

As Boki’s forests disappear in plain sight, the deeper crisis is not deforestation alone - it is neglect. The world watches, largely indifferent, while the Banyinyi women’s struggle keeps echoing a painful truth: we do not lack solutions, we lack the courage to abandon the myths of progress that blind us to them.

This article is part of a degrowth.info series on movements for social and environmental justice worldwide. Find out more and read the other pieces of the series here.

Walk Peace EU's marches for justice gather people together to walk across country borders and connect. This invitation to 'walk the talk' prompts us to question whether we live what we preach, then act on the insights gained during the walk.

In degrowth, we often speak about how the relationship between the Global South and the Global North could look differently. But what happens at the edges, and how can we understand these edges or points of encounter in the degrowth discourse?

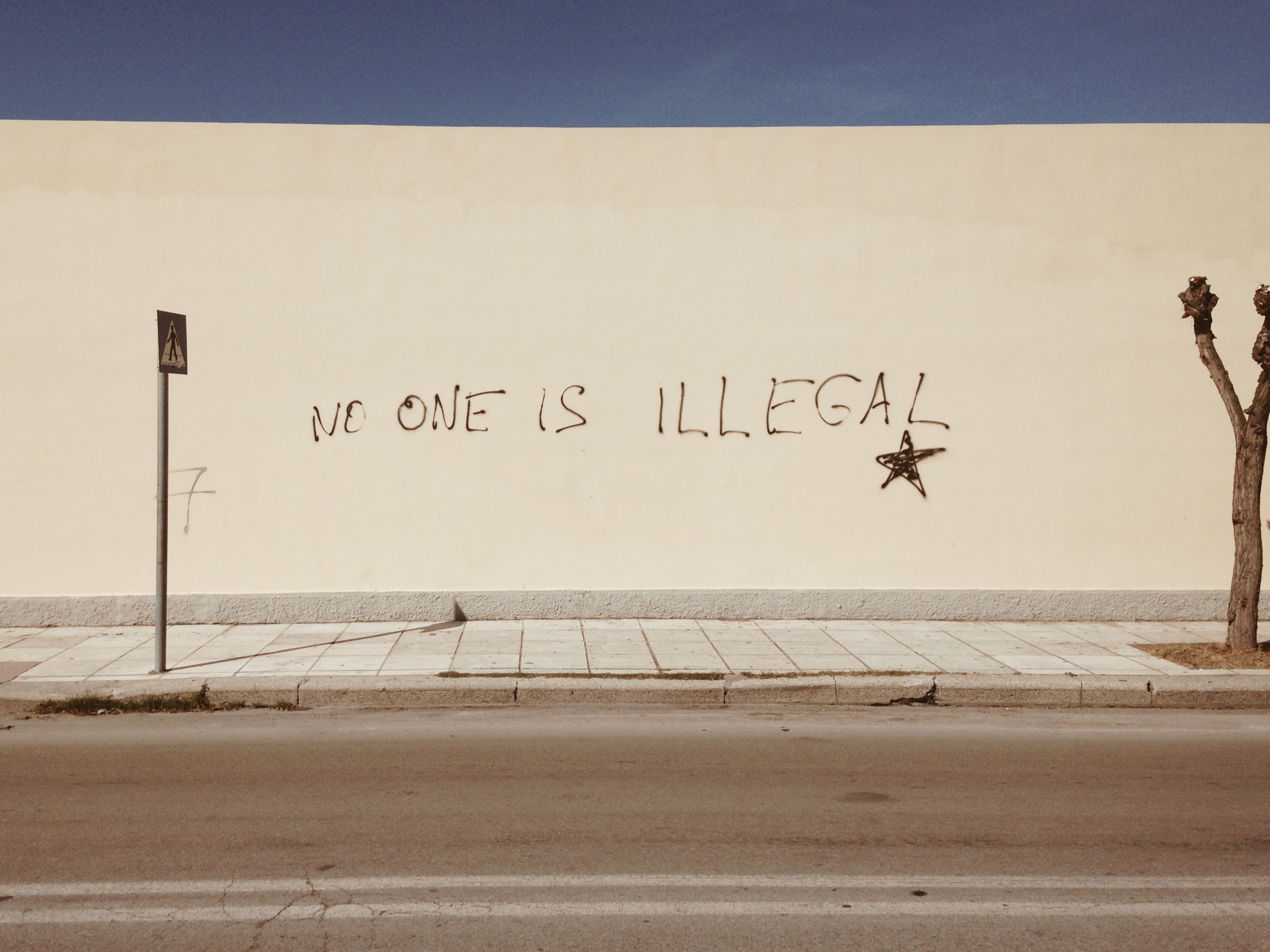

In the United States, the police-, prison-, and military-industrial complexes serve as the engine that fuels racial capitalism. The expansion of these various but interconnected forms of oppression rests on the subjugation of incarcerated and colonized peoples and on the exploitation of land stolen from Indigenous nations. The abolition of such is necessary in achieving an equitable and sustain...