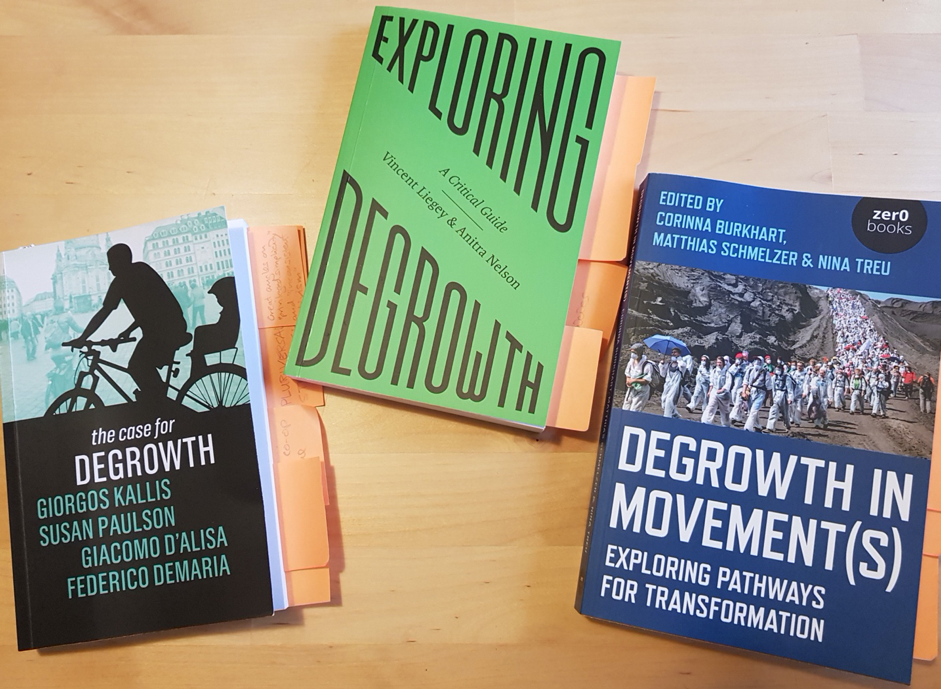

Hickel succeeds once more in making a clear yet robust case for degrowth, providing an accessible introductory text that the movement has long required. Degrowthers may remember 2020 as the year their ideas entered the mainstream, or at least the edges of it. As the coronavirus pandemic has prompted a renewed societal conversation around alternative futures, discussions of degrowth are increasingly popping up in surprising and high-profile outlets around the world. Whilst these appearances on major news sites are a recent development, the body of academic literature on degrowth is of course more mature and has been gradually expanding since the 2000s. Yet, something the degrowth movement has always seemed to be lacking is a general-purpose introductory text, suitable for recommending to any friend or relative curious to learn about the topic from scratch. Previously, I would always suggest Degrowth: a Vocabulary for a New Era, which is the book that introduced me to degrowth. It’s a fantastic resource which takes a glossary format, highlighting connections between degrowth and a wealth of other concepts. However, the book can leave readers who don’t already have a basic knowledge of fields such as political ecology and ecological economics feeling bombarded by academic concepts and with lingering uncertainties regarding what degrowth actually is and why we need it. But, as the British saying goes, sometimes you wait ages for a bus and then three come along at once. As well as all the stream of articles appearing in major media outlets, 2020 has also brought with it an explosion of new degrowth books, many of which seek to take up the task of delivering that long awaited introductory overview. One of these is Jason Hickel’s Less is More: How Degrowth Will Save The World. Published on an imprint of Penguin Random House, Less is More has the potential to achieve the greatest reach of any degrowth book to date. Hickel, an anthropologist based at Goldsmiths University in London, has emerged as one of the leading voices on degrowth internationally, but particularly in the UK. He gained a public profile through his 2017 book on global inequality, The Divide, which was well received by readers and critics. Since then, he has proven his capacity to make a clear yet robust case for degrowth through national media appearances, public events and his extremely retweetable social media posts. In essence, Less is More sees Hickel achieve this result once again, this time in a book format. First impressions At first glance, I wasn’t overjoyed with the framing of this book. While it may be catchy, the title Less is More risks playing into the common mischaracterisation of degrowth as representing ‘less of the same’, or recession. Additionally, the claim in the subtitle that degrowth ‘will save the world’ perhaps understates the difficulty of the struggle ahead. But hopefully this doesn’t knock would-be readers’ faith in the gravity of the arguments to come, and they arrive at the much more nuanced account developed in the text. It is a notable reflection of the current political moment that the book begins with a foreword from Extinction Rebellion (XR) spokespeople, Kofi Klu and Rupert Read. The links between degrowth and XR have been gradually strengthening over recent years, with Hickel himself appearing on XR’s podcast to discuss Less is More. There is a clear rationale then for making the connection explicit with XR penning Less is More’s foreword, though I have mixed feelings on this decision from the perspective of someone more deeply engaged in the degrowth movement than XR. On the one hand, the fact that degrowth is increasingly building alliances and finding resonance with major social movements is fantastic to see, as this will be crucial if degrowth is to have any influence on the direction of society in coming years. Having said this, degrowthers should also be conscious of the important critiques XR has received for its race and class privileges. Change seems to be happening within XR to address these issues, but nonetheless, the degrowth movement must be critical allies where necessary so as not to undermine its own work towards building alliances with movements around the world for racial and economic justice, which includes addressing degrowth's white euro-centrism. Diagnosing the crisis After the foreword, Less is More follows what will be a recognisable structure for frequent readers of non-fiction texts on the current ecological and social crises. It begins in the first half by identifying the problems and how they came to be, before turning to the proposed solutions in the latter half. For those already engaged in environmental movements and research, the depths of ecological crisis Hickel outlines in the book’s introduction will likely be all too familiar, serving as a gloomy yet crucial reminder of the truly existential catastrophe life on Earth is facing. Indeed, Hickel himself invites such readers to skim over this section should they desire. Following the introduction, in the first of six major chapters in the book, Hickel moves on to discuss the rise of capitalism and the resultant threat this presented to ecology. A logical starting point. He manages to do this, however, in a way which adds value to the standard accounts of capitalism one often finds in popular environmental books. Hickel’s anthropology background comes to the fore, as he traces humanity’s relationship with non-human ‘nature’ across centuries of civilizational change, pinpointing the key moments in which the cultural roots of our destructive attitude towards the rest of Earth’s biosphere took hold. This anthropological angle is a valuable addition to existing degrowth literature, which is dominated (albeit understandably) by economic framings. Hickel provides an important reminder that our problems run much deeper than the contemporary capitalist system alone, and rest in a centuries-old worldview which sees humans as separate from the rest of Earth’s lifeforms. At this point, Hickel turns to Less is More’s main subject of critique: growth. He charts the emergence of GDP growth as the foremost measure of societal prosperity, and the grave ecological crisis this has landed us in. Crucially, Hickel guides the reader through an introduction to a material footprint analysis of ecological degradation, making it clear that reducing carbon emissions is only one of many intersecting struggles we face. Aided by several useful graphs, Hickel evidences GDP growth’s enduring link with the material footprint of nations over time. Importantly, he anchors this critique of growth in a framework of colonialism, in which nations of the global North continue to expand their GDP through the exploitation of ecosystems and labour in the global South, and a grossly disproportionate claim on atmospheric commons. This pinning down of growthism’s colonial nature is another strength of the book, as Hickel leaves no doubt in the reader’s mind that our path out of ecological crisis must be decolonial in nature. Hickel rounds off the first part of Less is More by addressing those who claim that technology is the solution to ecological crisis. He spends most of this chapter focusing on the fallacy of carbon capture and storage, which was central to the 2015 Paris Agreement plans to keep global temperature rises below 1.5 degrees Celsius. At just over halfway through the text, Hickel now turns to his own proposed way forward. The degrowth proposition Hickel begins this section by demonstrating the wealth of existing evidence that high-income countries have long since passed the point where the connection between GDP and wellbeing breaks down. Hickel compares countries such as Costa Rica, where remarkably high levels of wellbeing are achieved with relatively low GDP, to countries like the US, which exhibit much poorer levels of wellbeing alongside an astronomical GDP and material footprint. Whilst this discussion kicks off the second section of the book, it arguably remains more a critique of growth than part of an alternative degrowth vision. It is after this problematising of the relationship between GDP and wellbeing then, that Hickel turns to Less is More’s core proposition. The bulk of this propositional chapter is anchored around what are effectively five policy proposals to advance a degrowth transformation of society. Each is well-articulated, and will undoubtedly leave readers with the feeling that there are concrete actions their governments could be implementing tomorrow in order to reduce significantly the destructive ecological impact of high-income nations, whilst vastly improving quality of life for all citizens. Seasoned degrowthers will likely already be familiar with these proposals, which are long established within the movement. While most readers will probably find little to disagree with Hickel’s proposal in terms of the policies themselves, this section is where my main reservations with Less is More emerge. By framing so much of the discussion around policy-oriented proposals, Hickel tends towards an account of degrowth as something to be implemented by state and supranational governments. Thus, for readers new to the topic, the book leaves unexplored some of the more rich and vibrant elements of degrowth such as its development as a movement constituted by activists, researchers and practitioners, and the agency it locates with decentralized bottom-up initiatives for social change. In other words, I would have liked Less is More to offer more inspiration to readers in terms of how they themselves could engage with the degrowth movement and take action at a grassroots level to advance degrowth aims. Additionally, Hickel offers little information as to how the policy proposals detailed will come about; how do they move from the page to reality, and who are the actors involved? But of course, no one book can be expected to capture the entirety of degrowth as a concept. It is fortunate then that Less is More has arrived alongside so many other texts which aim to introduce degrowth to new and wider audiences. For example, Hickel’s contribution will likely be able to establish complimentary relationships with other recent books such as Liegey and Nelson’s Exploring Degrowth, and Burkhart et al’s Degrowth in Movements, both of which frame degrowth from more of a movement perspective. Much like Hickel argues in the final chapter of Less is More, everything is connected, interdependence is key. Perhaps this applies to the expanding repertoire of degrowth books as well as humanity’s relationships with non-human nature. Returning to his anthropological expertise, Hickel closes Less is More by highlighting the inspiration that can be taken from those who have long demonstrated ways of living sustainably alongside the other lifeforms and ecosystems on this planet, such as indigenous communities in the global South. He points to the joyful potentialities that are opened up when we as humans conceive of ourselves not as separate from but as part of one living world full of wonder and diversity, which we must play our part in nurturing. Rather than falling back on troubling statistics and warning cries, Hickel makes a compelling plea to our better nature, signaling the extraordinary futures open to us if we can divert our societal path. It is exactly these kinds of emotive narratives that the degrowth movement needs to employ more often and effectively if it is to build a critical mass of support. For the degrowth-curious and beyond As I see it, Less is More isn’t a book for degrowthers; though many will of course enjoy reading it. The most valuable contribution of Less is More is that it provides an accessible and compelling introduction to ecological and social critiques of growth, and how degrowth could address these, for anyone who is remotely interested in a liveable future on this planet. Beyond the degrowth-curious then, this is a book that I can easily see becoming a staple of introductory reading lists on our current ecological crisis and ways forward. An introduction it certainly is though, and hopefully, for most readers Less is More will be just the start of their exploration of degrowth, rather than the full extent of it. Still, from a degrowther’s point of view, the arrival of Less is More means that you will no longer have to persuade your friends and relatives to wade through stuffy academic jargon for them to understand why you won’t shut up about this ‘degrowth’ thing. Jason Hickel has us covered.

While it is now largely clear what degrowth is striving for, how to realize the transformation towards this end state has not been engaged with satisfactorily. The Future is Degrowth (TFiD) and Degrowth & Strategy (D&S), two books that now complement the burgeoning popular literature on degrowth, set out to find answers to this underexplored question.

In November 2021, more than 4.5 million people voluntarily left their jobs in the US, the highest number since records began. Popularly known as the ‘Great Resignation’, the ongoing rejection of work-as-we-knew-it may not be a social movement in the normal sense of the term, but it is certainly a sign of rolling social upheaval. The increasing bargaining power of labour in the Covid economy, an...

A year ago, in August 2020, we launched our jointly authored book Exploring Degrowth: A Critical Guide (Pluto Press). ‘The book you hold in your hands’ states Jason Hickel of the University of London and author of Less is More 2020, ‘paints a picture of the new economy that lies ahead — an economy that enables human flourishing for all within planetary boundaries.’ Discussion about degrowth has exploded since then when a cluster of general interest books on degrowth appeared in 2020.