On August 14th, an uprising of art installations and happenings emerged in the Old North End neighborhood of Burlington, Vermont. Two days later, they all disappeared.

Through these art pieces, community members and local organizations explored today’s tensions and possible paths toward desirable futures. Burlington residents navigated the neighborhood on self-guided tours, following a map of all the paintings, sculptures, ephemeral performances, and interactive creations. The event was called DegrowthFest 2020.

Our neighbors took interest in degrowth. It was an occasion for community education, reflection, and imagination in a way that it could not have been had the event gone as originally planned.

DegrowthFest was supposed to be, well, a festival. At beginning of 2020, the group organizing the event – DegrowBTV, of which I’m a part – was planning to host a few hundred people for a weekend of music, talks, art, campfires, workshops, disobedience, and conviviality. We expected that folks from all over who were already interested in degrowth, plus some degrowth-curious locals, would show up to share ideas and good times.

Then Covid happened. We didn’t cancel DegrowthFest, but we stopped all planning and preparations. Back in April and May, no one knew what would be possible to do safely August 14 to 16.

Then in June, our seven-person collective of activists, academics, and artists started to meet again, outdoors, yelling to each other across spaced-out circles. Together we envisioned a Covid-safe DegrowthFest, centered in the community.

Meg Egler and Sam Bliss of DegrowBTV preparing materials for DegrowthFest

We distributed two-by-two foot white plywood squares to interested people and organizations, who could make art on this canvas and beyond it in response to our three prompts, which were partly inspired by a Bruno Latour blog post: What has been revealed? What will be brought forward? What will be left behind?

What folks created was astounding. The Burlington Tenants Union’s Emily Reynolds made a framed painting of a house that said, “Everyone needs a home. No one needs a landlord.” Jess Morrison of the Vermont Workers Center carved an intricate block print about people power titled, “You only get what you’re organized to take.” On her home’s porch, local musician Katy Hellman strung up driftwood marionettes called “the dancers” and accompanied them with a poem. Black Lives Matter of Greater Burlington and BTV Copwatch (a group that films the police to hold them accountable) collaborated on an interactive art-making and information table to raise awareness about their “Think twice before you call the police” campaign.

Others set up public comment boxes, painted utopian landscapes, quoted transformational books, fashioned 3-D art from found materials, and told fantastical stories to tiny audiences. You can see all the contributions, and make your own, in the virtual degrowth gallery we’ve put together.

Before the coronavirus broke out, we had already intended to engage our neighborhood in DegrowthFest, but it was a beautiful accident that the pandemic forced us to make it an event to which we invited only our local community. Our event sparked conversations about our collective future, and about degrowth.

Many artists’ contributions engaged with degrowth, even though the prompts we had given them did not mention the term. On his canvas, local resilience advocate Jan Schultz simply pasted a Stan Cox quote that included the line, “Whether we set off on the journey calling for the end of growth or the end of capitalism, we’re checking our bags to the same final destination (preferably on a train).” My housemate Becky Miller created a pyramid of actions to “reconsider consumption” – from doing without to using what you have, to borrowing, making, and buying secondhand or repairable products. Another contribution, from the artist Kim Marie Glynn and Mycoevolve’s Jess Rubin, framed an adorable ecological scene with a sun inscribed, “Degrow human footprint, create space for other kin.”

People were curious about degrowth. Festivalgoers stopped at our Degrowth Info Booth to talk to a DegrowthFest organizer or grab a copy of our cute “What is degrowth?” zine. Our unhoused friend Leslie took interest and went on a guerilla flyering mission with a short statement she had written about the economics of degrowth. Comrades at the Black Lives Matter and Copwatch table told us they talked with each other and passersby about degrowth all day – about the concept’s resonance with defunding the police, about its relationship with racial justice, about what degrowth might mean for the neighborhood.

DegrowthFest installation by Emily Reynolds of the Burlington Tenants Union

Different attendees interpreted degrowth differently. For some locals, rejecting growth as a primary goal for the city of Burlington could release us from the rule of developers, business leaders, and their allies in municipal government, opening creative space for transformation toward justice and sustainability. For ecologists like Rubin, degrowth meant challenging the idea that humans – rich white men in particular – get to be the rulers of the land we share with all life. Younger activists’ conceptions of degrowth often involved reviving the traditional practices and simple technologies of this region’s Indigenous peoples and its settler homesteaders, combining old wisdom and new thinking.

These diverse intuitions mirror the plural understandings of degrowth in the academic literature: the Barcelona school’s anti-capitalist degrowth, Eileen Crist’s reversal of human expansionism, Samuel Alexander’s voluntary simplicity or Ivan Illich’s tools for conviviality, to name a few parallels.

Degrowth resonated with many people in our community. That is the remarkable result of DegrowthFest, for me. I am thrilled but not surprised that so many friends and neighbors were keen on this movement and idea that is so dear to me.

Others might disbelieve that ordinary people are into degrowth. Very serious online intellectuals who dislike degrowth tend to criticize the concept not because they don’t get it, but because they think the less-educated masses won’t.

Yet it turns out that many folks think degrowth makes sense. We are probably not enough people to win an election, but plenty for a movement. As a movement among movements, we can be powerful, collectively.

The progressive academics and journalists who say that “people” or “others” will not go for degrowth should turn their reflections inward. It is they who are averse to degrowth. Rather than projecting that rejection onto an abstract common person, they should own it, and explain what they dislike about degrowth.

What’s more, thought leaders influence people’s opinions. When they say that degrowth will be unpopular it can become a self-fulfilling prophesy.

"Consider NOT Consuming" by Becky Miller

On the other hand, when we invited the public to participate in something called DegrowthFest, but didn’t tell people what to think, we found that degrowth was enticing. It elicited curiosity. Imagine what would be possible if the media and public intellectuals presented degrowth even neutrally, instead of degrading it and assuming that it evokes fear.

I think we degrowthers sometimes get swayed by this idea that degrowth is scary to people. We rush to explain it, to clarify what it really means, afraid that our audience will be afraid by the word degrowth, that they will think we mean recession or enforced poverty or “going back to the caves.”

DegrowthFest provided some evidence that many people do not need experts to tell them what degrowth is or is not. Conversations with friends and strangers reveal that the uninitiated often have a good sense of what degrowth might mean.

Of course we are working with a biased sample, a self-selected group whose ears perked up when they heard “degrowth” spoken or saw it on a poster. But if we are trying to spark a movement, then it is good strategy to focus our attention on the people for whom our cause already resonates.

Inviting interested people and potential allies to define degrowth welcomes them to our group. It starts a conversation, sometimes even generates novel ideas.

This was the first activity we did at the 2018 Degrowth Gathering in Chicago, the first ever event put on by our loose collective, DegrowUS. Everyone wrote what “degrowth is” to them on a sticky note. I still have those post-it degrowth definitions and they are beautiful.

I get that we want to differentiate our emancipatory degrowth vision from misunderstandings that might involve limiting immigration or authoritarian measures. My point is that maybe we should listen first, and trust that there will be a chance to speak.

"Ethically Rewilding Our Neighborhood" by Kim Marie Glynn (artist) and Jess Rubin (garden designer and installer), of MycoEvolve

DegrowthFest opened space for our neighbors and comrades to speak. People expressed what today’s intertangled, slow and urgent crises reveal, and dreamed desired worlds for us to co-inhabit.

Burlington’s streets became a free forum for many communication forms. Walking around the neighborhood on a scavenger hunt for DegrowthFest installations, I noticed all sorts of art that I had not before, on streets I’d walked dozens if not hundreds of times.

The late intellectual giant David Graeber once wrote, “The principle of direct action is the defiant insistence on acting as if one is already free.” We did not ask the city for permission to put up art for the weekend; instead we talked directly to our neighbors about temporarily installing pieces of our spread-out art festival in front of their homes, inviting everyone to participate as we went.

One of DegrowthFest’s organizers, scientist-artist Kristian Brevik, likes to say that the medium is the message. In this case, perhaps much of the point was to lure people out to walk around their neighborhood, to peruse not just the fleeting installations but the beauty that is always there.

Together, we donned glasses through which we saw a degrowth future latent in our own community, if only for one weekend. I am happy we didn’t do a web conference instead.

Members of the degrowth.info collective offer some reflections on the 2025 International Degrowth Conference

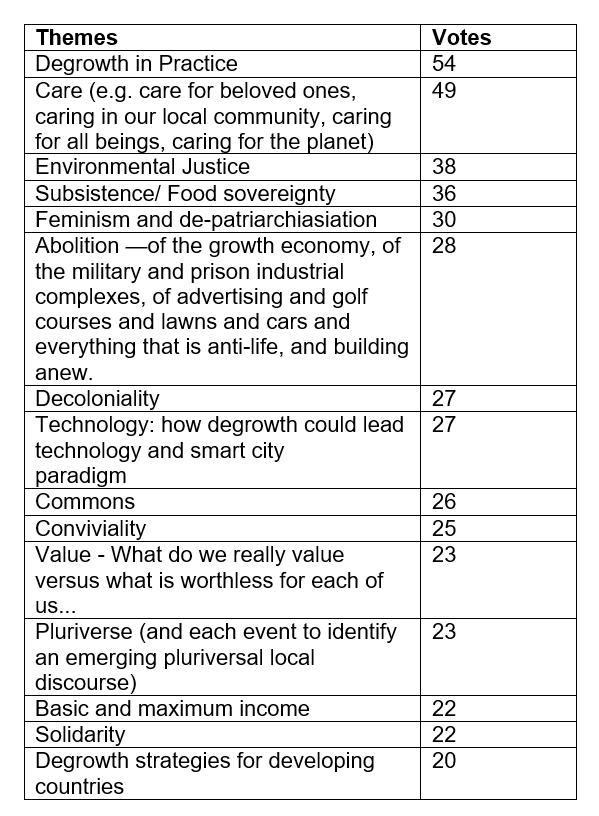

In this announcement, the Global Degrowth Day organising team talk through the selection of care as the theme for the 2021 edition of the event. In our search for a theme for next year’s Global Degrowth Day, taking place on June 5th 2021, we launched a call for ideas back in October, and a poll in November. These were the results: The results reflect the multiple angles and aspira...

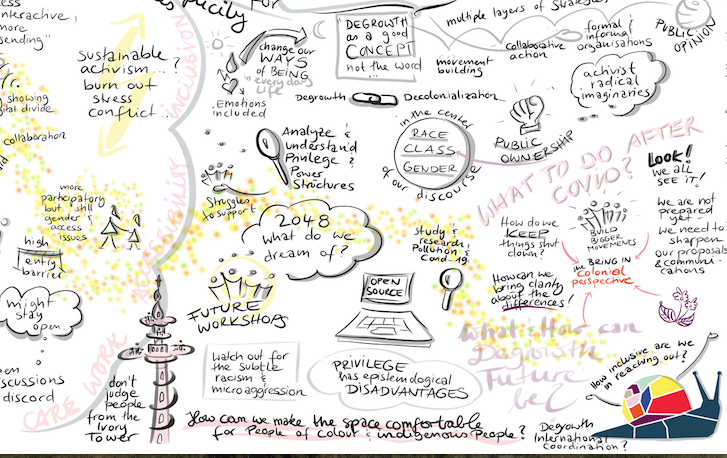

This is part two of a piece reflecting on the Vienna degrowth conference and considering how to move forward based on the inputs and insights from the conference. You can read part one (focused on the conference) here. The idea of organizing the Degrowth Vienna 2020 conference was at least in part connected to a piece that some conference organizers published in this blog in which they crit...