In the United States, the police-, prison-, and military-industrial complexes serve as the engine that fuels racial capitalism. The expansion of these various but interconnected forms of oppression rests on the subjugation of incarcerated and colonized peoples and on the exploitation of land stolen from Indigenous nations. The abolition of such is necessary in achieving an equitable and sustainable world, in transitioning to a degrowth society. But as long as capital severs any possibility of harmonizing with the very land that feeds us, Black and Indigenous people will continue to die at the hands of the white supremacist project that is the United States. Before the American Civil War, there were slave patrols in southern slave-holding states. White Americans volunteered to enforce the ‘property’ rights of slave owners, using vigilante tactics that were encouraged by the state. After the Union won and the 13th Amendment was passed, Jim Crow Laws maintained the subjugation of Black people through Black Codes, a set of local and state laws that “detailed when, where and how formerly enslaved people could work, and for how much compensation.” Even with the landmark 1964 Civil Rights Act—which ended segregation in public places and banned discrimination in housing, employment, education, and other areas on the basis of race, color, religion, sex or national origin—the mass incarceration machine kept slavery alive through the 13th Amendment, which contains a convenient clause that justifies the enslavement of Black people through their violation of the law, creating a massive carceral system that profits off of prison labor. While slave patrols no longer exist today, the creation of the police force serves to extend the state’s control over property. Neither the vigilantes of the pre-Civil War Era nor the police officers of today function to protect human lives. Rather, contract law in the US creates the language and structure that maps out property rights, and the police are there to enforce the law and protect private property. Although the concept of private property is not inherently unique to the United States, its roots in the US have long been entrenched in the colonization of native people. As American colonizers were carrying out ‘manifest destiny’—a cultural belief dating back to the 1800s that justified the extension of the US Empire throughout the continent by way of Ingidenous genocide—they were also engaging in the slave trade. This expansion of American imperialism and racial capitalism reveals a deeply intertwined relationship between the pillaging of Native American soil and the country’s use of slave labor to exert control over it. Through these exploitative processes, humans’ relationship with the land took a fundamentally different turn. While we could live in balance with the earth, creating community gardens and building housing for the homeless and the poor, capitalism compels us to find room for fossil fuel extraction and provide office space for corporations that profit off of environmental destruction. It’s important to note that there is no such thing as a ‘green building’ if it primarily functions as a space for corporate executives to meet and decide how to exploit the people and the planet. Moreover, we have dedicated entire islands and swathes of land to build prisons and colonize other parts of the world for military bases. So long as the belly of the beast will never be satisfied, the US government will continue to test the limits on how it can treat the earth and the people, especially Black and Indigenous people, who are living on it. What are the limits, if there are any at all, to their treatment? We know all too well that there are no limits. In a country that runs on GDP growth, the economy is portrayed as the lifeline for all workers. Without constantly high consumer spending, how are people going to feed themselves and their families? In Kenosha, Wisconsin, where police officers shot Jacob Blake in the back seven times, automobile manufacturer Chrysler had been a major employer in the city, attracting many Black and/or Latinx workers who were drawn to the city through the union jobs they had offered. However, in 2009, the Obama administration’s bailout of Chrysler, which merged with Fiat, outsourced hundreds of jobs from the Kenosha engine plant to Mexico. Its permanent closing in 2010 left 5,000 people out of work. In the aftermath of Obama’s bailout of the automobile industry, the former president proved successful in easing the concerns of investors, but provided little relief for the workers in communities such as Kenosha who were stripped of their union jobs. The bailout of automobile companies helped ‘save’ the economy, but millions of workers suffered from the consequences. The arrival of Amazon in Kenosha in 2015 generated 4,000 new jobs, but the big employer has long remained notorious for its list of workplace abuses and low wages. Moreover, Amazon is a member of the executive committee of the Seattle Police Foundation’s board, is a partner and donor, and contributes to other police foundations across the country through its charitable giving program, AmazonSmile. The big tech company has also been widely criticized for providing facial recognition software to police. Under the growth paradigm, what has been lost in GDP can be made up for in GDP. In other words, the drop in human well-being does not factor into the bigger picture of an economy that only cares about profit and production. This endless pursuit of profit undergirded by racial capitalism and the colonial project has catapulted us down the path of accelerating ecological disaster and deepening socio-economic inequity. Global warming will open up more water ways, providing even more trade routes. Climate change will continue to benefit the corporations and the rich, until there are no more consumers to sell to. Meanwhile in Kenosha, there are polar vortex deep freezes, record-breaking snowfalls and summer rainfalls, and coastal erosion, with more to come. Climate justice demands racial and economic justice, as part of a broader and deeper examination of the global economic order as it stands today. We must instead create a sustainable path of living, in which humans can harmonize with the land they live on. This means the abolishment of the carceral system. So long as carceral structures exist, Black, Brown, and Indigenous people will continue to be denied access to stable and affordable housing and the ability to get the care they need. Instead, they will always be given a place in one of America’s 2,148,000+ prisons and jails. These prisons are located far from places of community. If we had to pass by a prison with windows every time we walked to the nearest grocery store, we would react far more differently to the injustices being done. Instead, prisons are located strategically, taking advantage of the vast land controlled by the state in order to create a comfortable distance between those who can move and those who cannot. This continuous siphoning off of parts of the world to imprison and isolate people is unfeasible, and we would do better in repairing broken land, in abolishing these carceral structures. But abolition is not an end in and of itself. It is the beginning of a reparative process of healing that reconciles human error with human need, that replaces human disposability with human dignity. It is hard to imagine what the future looks like with all the smoke from the wildfires, but several things are clear. First, the United States must pay reparations to Black Americans for their ongoing enslavement, which is maintained through prison labor. Secondly, they must provide land reparations and land returns to Indigenous peoples here. Lastly, we must abolish the police-, prison-, and military-industrial complexes in order to prevent further harm and clear the pathway for a better future. Just as how capitalism exploits Black labor to make as much profit as possible, abolition under a degrowth society would end the cycle of poverty and redistribute the wealth among the people in an equitable manner that confronts racial inequalities. Ultimately, the degrowth of the US is impossible unless we reckon with white supremacy’s fetishization of private property and economic growth—it is impossible unless we strive towards a racially-just world.

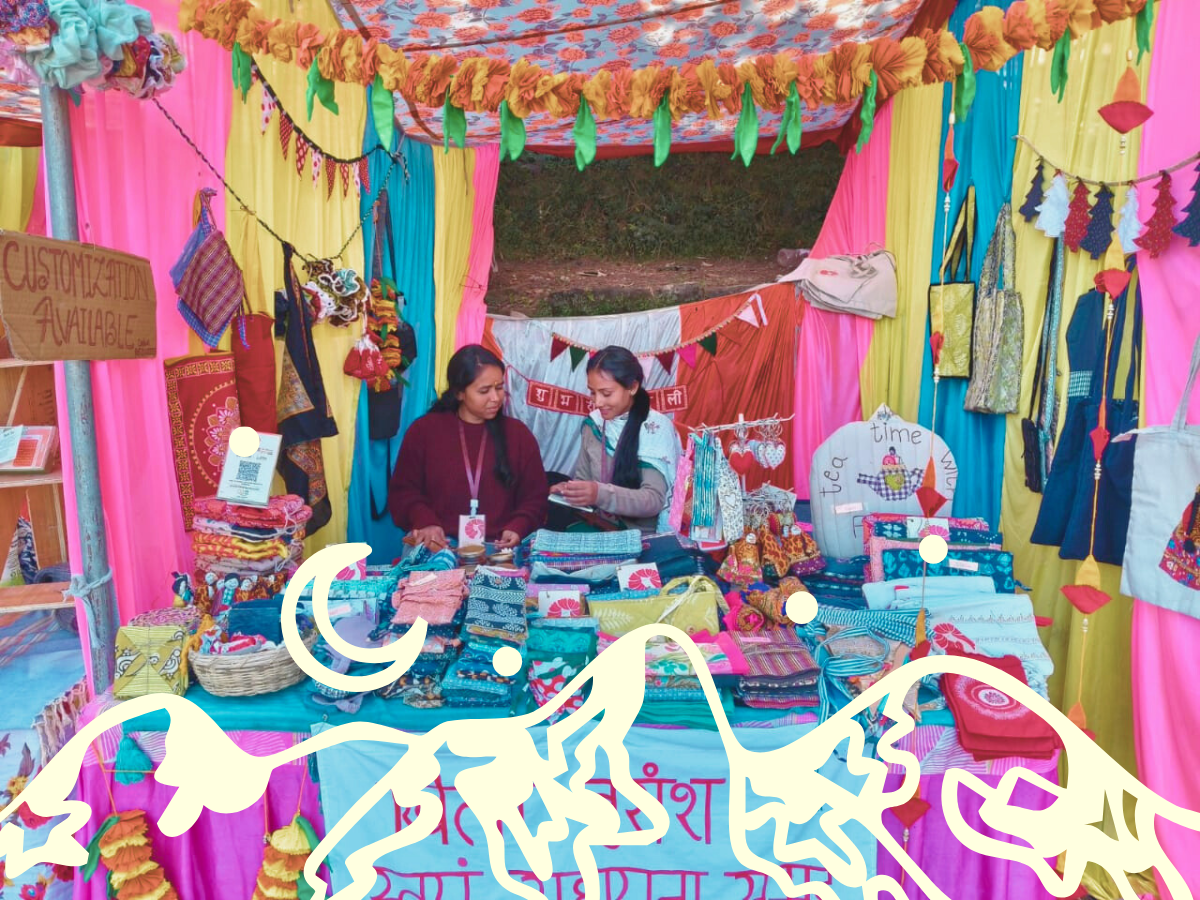

In this article, Shruthi documents the work of an empowering self-help group, Khili Buransh, in a remote Himalayan village in Uttarakhand, India. Shruthi explains how Khili Buransh leads a silent revolution against the prevailing capitalist-intensive, extractive, patriarchal, and casteist system.

Reconciling degrowth and law isn’t always easy, given the anarchist underpinnings and anti-statist leanings of some in the degrowth community. One vision of a degrowth world is of decentralized, autonomous, convivial communities of people in tune with their supporting ecosystems, consuming no more than they need, sharing as much as possible and treating each other with compassion, fairness and mutual respect. No central state power, no police, no borders, no masters and servants, no conspicuous consumption, no oppression. This, however, doesn’t necessarily require a world without law, just a world with law that is much different from the forms of law that prevail in today’s rapacious and unjust world.

In the midst of the COVID-19 crisis, violence against women is increasing. More women are isolated at home with abusive partners and without resources and opportunities to leave. In Canada, where only a few months ago funding for Ontario rape crisis centres was slashed by $1 million, the political pressure to intervene in gendered violence has increased. Many women’s organizations, such as the ...