Degrowth scholars and activists often turn to past cases of social or socioecological transformation for inspiration to inform transformative action in the present. Yet, there has so far been insufficient awareness of the bias that comes with using any historical analogy. The insights provided by historical analogies are limited, but can fruitfully complement analyses of the present and future-oriented visions of societal change.

As degrowth scholars and/or activists, we often turn to past cases of social or socioecological transformation for inspiration to inform transformative action in the present. This approach — to look back to the past for ‘lessons’ or insights on possible strategies — is not uncommon in sustainability studies.

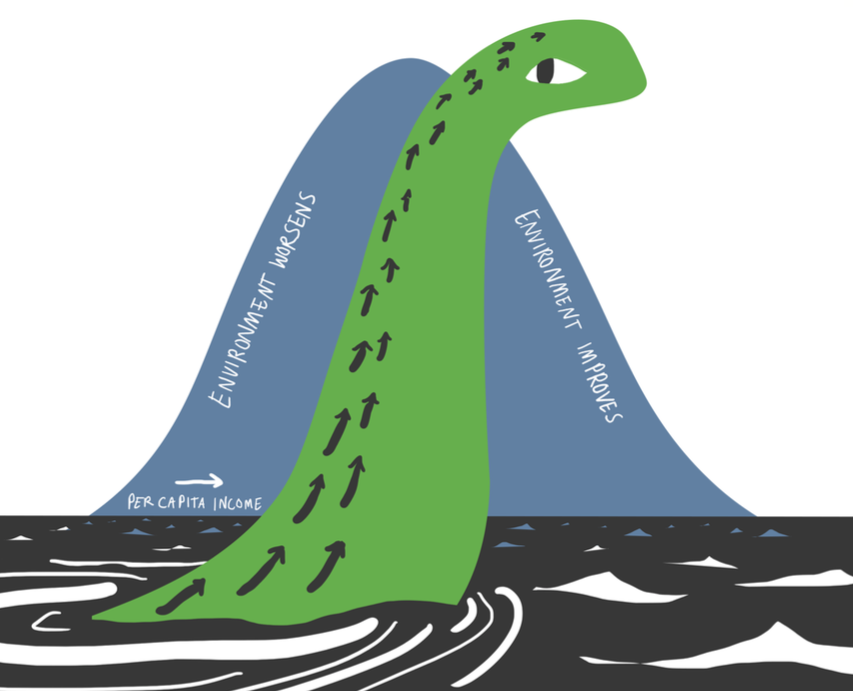

However, it is apparent that there is no single most appropriate historical analogue of a degrowth transformation. The concept of a degrowth transformation has been associated by scholars with diverse historical analogues such as the agricultural revolution, the abolition of slavery, and the Great Transformation which saw the expansion of the market society (after the work of Karl Polanyi), among others.

There are various reasons for these diverse comparisons. First, there are a plurality of understandings of what a degrowth transformation may look like in practice, which multiplies the pool of possibly relevant historical examples. Second, there is the unprecedented character of such a transformation, and specifically, the fact that degrowth implies societal change beyond, rather than within, capitalism; a type of transformation of which there is hardly any historical experience.

In fact, no one historical analogue is inherently more relevant or appropriate than others when it comes to deriving insights into the conditions and processes of fundamental socioecological change towards sustainability. However, it can be noted that past experiences of social and socioecological transformation differ from each other in various respects. For example, different historical analogues may offer contrasting insights into:

- - which societal ‘system(s)’ can undergo transformation (e.g. a community, a national society, global society, an industrial sector, a political regime, a cultural paradigm);

- - how long transformations take (e.g. years, decades, centuries), and to what extent transformation entails ecological, political, economic or cultural catastrophes (e.g. financial crises, the collapse of a political regime or of an ecosystem);

- - whether the primary force behind transformation is internal (e.g. actors within the economic or political system that undergoes transformation), external (e.g. broader ecological or economic shocks) or a combination of both internal and external forces;

- - whether transformation can be the result of deliberate action by particular social groups, or is rather necessarily the result of complex, uncontrollable social dynamics;

- - what the end result of transformation looks like (e.g. change of social structures, cultural practices, social justice, etc.)

For example, would a degrowth transformation be more like a deliberate social mobilisation over a relatively short (in historical terms) time period, such as the abolition of slavery, or a long and emergent process such as the agricultural revolution? Would a degrowth transformation be more likely after an ecological or socio-political collapse, like the transition of Central and Eastern European countries after the fall of the Soviet Union? Will it be more like a national liberation movement? Will it advance through single-issue struggles, such as the affirmation of social rights through struggles around race, gender and labour?

The insights we can derive from such different historical analogues would differ significantly with respect to, for example, the actors and coalitions driving change, the extent to which idealistic or materialistic motives can drive which type of social change, the timeframe of change, and whether social or socioecological transformation can ever be managed or even steered deliberately in the first place.

Therefore, the exercise of selecting a particular historical analogue is inherently laden with assumptions about the type of transformation pathway we might expect to observe in the future. Yet, there has so far been insufficient awareness of the bias that comes with using historical analogies. To respond to that fallacy and advance our thinking on the conditions and processes of a degrowth transformation, we are therefore challenged to develop an approach to using historical analogues.

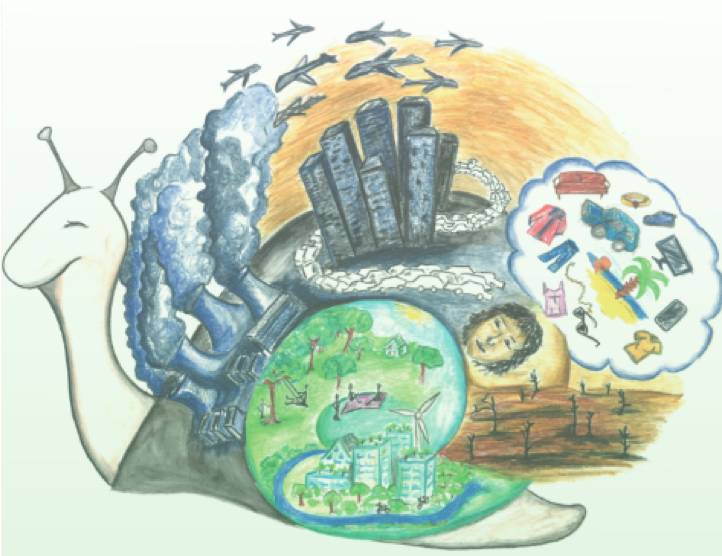

It is important to consider that any ‘lessons’ learned from studying historical analogues may be narrowing our perspective, and missing the productive interconnections that exist in the present historical period among different forms of ‘actually existing’ degrowth (in grassroots initiatives, as a scientific paradigm, and a social movement). For example, the recent move towards knowledge co-production between practitioners and scientists, across much of the social sciences, as well as in research on degrowth, can be seen as a novel form of interconnection between degrowth as a social movement and as a scientific paradigm, which can reinforce processes of change in ways that were not possible in the past due to different social scientific practices. Similarly, rapidly developing global forms of online communication, which facilitate both social movement organisation and the spread of ideas, hardly have any historical precedent that matches the geographical coverage, speed and penetration in everyday life, but represent an important tool for the interconnection of these different social

movements that can be allies of degrowth.

How should we deal with historical analogues? First, we need to be aware that, as there are multiple possible degrowth futures and pathways, there are also multiple possible historical analogues to learn from. Second, we may want to refrain from attempting to derive deterministic ‘lessons’, as there are

hardly any ‘natural laws’ of social change. At most, we can hope to be inspired by understanding how past social and socioecological transformations occurred, while acknowledging that the mechanisms that caused social change in the past may not be the ones that lead to social change in the future.

Third, the limitations posed by the use of historical analogues urge a reconsideration of the balance between

past-oriented research and thinking, and exercises of

‘futuring’ for degrowth, including modelling. The degrowth community can place more effort in using insights on how societies changed, and visions of how we desire them to change in the future to ‘stress-test’ each other: historical analogues can provide grounding for developing visions of the future, while the visions of the future can expand the range of conceptualisations of transformation pathways beyond what we could otherwise conceive on the sole basis of past transformations. When insights from past, present and future become meaningful in relation to one another, historical analogues are a useful complement to our understanding of societal change.

This short piece draws from an earlier paper presented at the 13th International Conference of the European Society for Ecological Economics in Turku, June 2019.

This article is part of a series on degrowth.info discussing strategy in the degrowth movement. The introduction to the series and an ongoing list of contributions that can be found here.