It’s been about a week since the 2020 presidential election in the United States was called for former-Vice President Joe Biden, and the dust has anything but settled. As a new presidential administration prepares to replace the current one (which has openly declared its refusal to leave), where does this leave the degrowth movement in the United States? I was in the middle of a reading for one of my classes when I found out the news on Saturday, November 7th. Opening up Twitter to take a break from some Ivan Illich, I saw that my timeline was filled with people discussing Biden’s win. Many were celebrating the symbolic ousting of President Donald Trump, while many others were critiquing the outcome, highlighting the fact that the U.S. still remains a capitalistic settler colonial empire, no matter who stands at the helm of this country. Also populating my feed were the reactions from President Donald Trump and his camp, denying the validity of the election. This contestation of the election results remains ongoing at the time of this piece’s writing, with Trump’s campaign filing over a dozen lawsuits in more than five states. Many of these cases have been dismissed in state courts or abandoned by Trump campaign lawyers. Other escalations leave many people (myself included) wondering just how tumultuous of a transitory period the U.S. is about to enter, like Trump’s firing of people in key positions such as the Secretary of Defense and the Administrator of the National Nuclear Security Administration, as well as pro-Trump and anti-election-results rallies across the country (with the one in D.C. featuring violent confrontations between Trump supporters and counterprotestors). And to be honest, I’m still working through how I feel about the election results. I understand how a Biden win can be seen as the more preferable outcome in the realm of federal electoral politics, but the president-elect is by no means an ally of socioecological transformation. When considering Biden’s past misdeeds (like his record of constructing federal policies that supported the war on drugs and mass incarceration) and current causes for concern (like his corporate executive-stuffed transition team, climate plan pervaded by growthism, and infamous assurance to rich donors that “nothing would fundamentally change” if he secured the presidency), it becomes clear that the Biden administration will continue the rampant ravaging of land and people in relentless pursuit of capital accumulation. With this in mind, is it worth celebrating when the ceaselessly violent set of institutions, practices, and beliefs that lie at the putrid core of the United States simply changes its face? Once again: the United States of America—henceforth written as amerikkka (to call a spade a spade)—exists as the product and perpetrator of untold amounts of harm. As Indigenous scholars Nick Estes and Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz write, amerikkka stands as “the first nation born entirely as a capitalist state with a burgeoning and land-hungry plantation economy, a nation, in other words, built by Indigenous genocide and African labor, the legacies of which are now being struggled over on the streets.” Therefore, it can be said that amerikkka stands as a significant obstacle on the socioecologically liberatory paths tended to by degrowth movements. How, then, can degrowthers living in the imperial core of amerikkka effect change? As presidential power swings from one corporate party to the other, how can we work towards ensuring that the Biden administration is the last amerikkkan corporatocracy, thus putting an end to the amerikkkan settler colonial project? In short, what does degrowing amerikkka look like? Giacomo D’Alisa and Giorgos Kallis provide some insight regarding these matters in their paper that presents a theoretical understanding of the state in relation to degrowth transformations. Drawing upon Antonio Gramsci and Erik Olin Wright, D’Alisa and Kallis describe the state as a relational entity comprised of “heterogenous social forces and organizations that operate, more often than not, against each other [as a] result of conflicting relations and ideological struggles.” They go on to write that transforming an oppressive state into a more convivial orientation “requires a cultural change of common senses through the creation of new alternative spaces and institutions and the generalization of these changes through intervention at the level of political institutions”—a combination of efforts that both erode and tame the state (to borrow language from Wright). In other words, dismantling and transforming amerikkka necessitates two simultaneous paths of action: (1) the cultivation of local, on-the-ground initiatives that help people meet their social and material needs, thus opening up their minds and hearts to the possibilities of alternative ways of living and (2) the passing of policies within existing political systems that enable and facilitate these alternative ways of living. Indeed, both of these paths (and more) have been the subject of much discussion in the strategy debate within degrowth movements. In an attempt to contribute to this ongoing discussion, and drawing upon the guiding questions developed at Degrow Empire’s first political education meeting, here are some questions I’ll offer that are specifically centered around degrowth strategy in amerikkka:

Celebrate degrowth on June 4th 2022 - this year’s Global Degrowth Day! We call on everyone inspired by degrowth to organize (online) actions and events invoking the theme of Climate Justice. As usual, on Global Degrowth Day you are invited to explore the different ways out of growth-dependency, and to connect to inspiring (local) initiatives working on new paradigms relating to sustaina...

This summer, the 8th International Degrowth conference took place in Den Haag. This summary provides a peek at some of the important themes, take-aways, and points of contention discussed in the conference reportage co-published by the organisers Transnational Institute and Ontgroei.

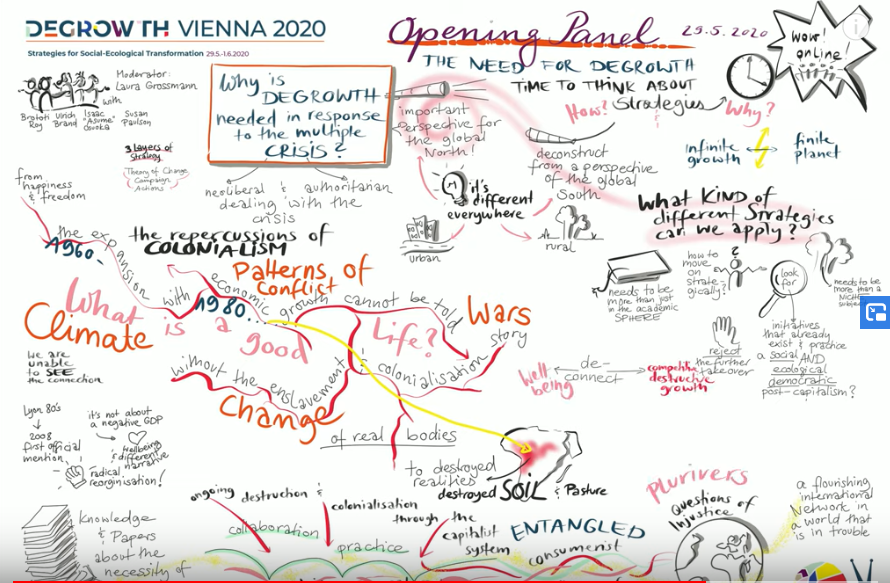

The conference “Degrowth Vienna 2020: Strategies for Socio-ecological transformation” took place online between May and June 2020, in the midst of a pandemic crisis. This two-part piece will firstly reflect upon the conference (part I) and then propose ways to move forward (part II). As a member of the Advisory Board, I was partly involved in the discussions regarding the planning of the...